Preparing for the "Olympic Class" Liners

Before comissioning the "Olympic Class" Liners, the WSL wanted to use the most suitable engine. Advances in technology had develoed the Triple expansion engines. WSL decided to commission two ships, the Laurentic and the Megantic and fit them with a different type of engine, as an experiment to see which one was best for the “Olympic class” liners still in the design phase.

The Megantic was a common functional twin propelled ship. The Laurentic had three propellers and a four cylinder triple expansion engine. Triple expansion engines were seen to be more efficient following the voyages of Laurentic and Megantic. Triple expansion engines were to be used on all three of the “Olympic class” liners.

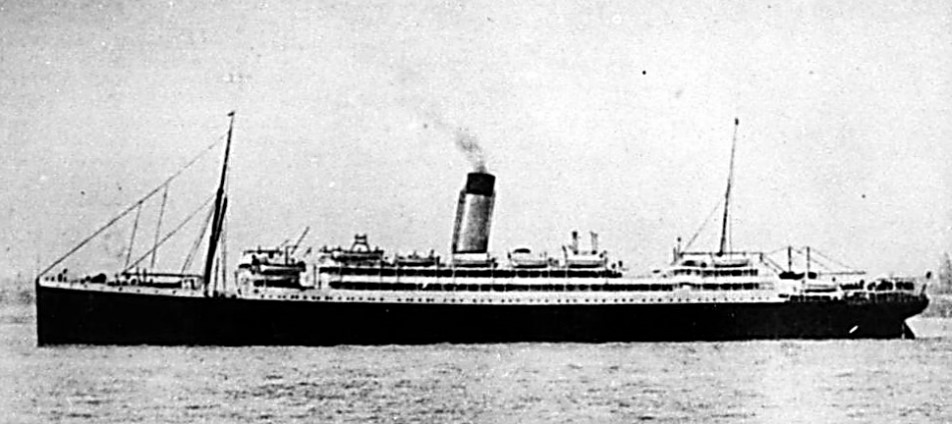

RMS Laurentic (1908)

The Laurentic was built by Harland and Wolff under keel number 394. She was launched on 10 September 1908 and completed on 15 April 1909. She was 565 feet long with a beam of 67.3 feet and had a gross tonnage of 14,892. She had three decks. She had a triple expansion steam engine capable of an average speed of 16 knots which was built by John Brown and Co of Glasgow.

Initially, the ship was owned and commissioned by the Dominion Line Steamship Company which they operated a passenger service from Liverpool to Québec and Montreal, Canada. During their ownership, the ship was called Alberta (her sister was Albony). During construction, the WSL purchased the sisters and changed their names to Laurentic and Megantic.

On 20 April 1909, Laurentic commenced her maiden voyage from Liverpool to Québec. She carried 1057 passengers. Predominantly, she served the Liverpool to Canada route until the winter months when she would stop at New York.

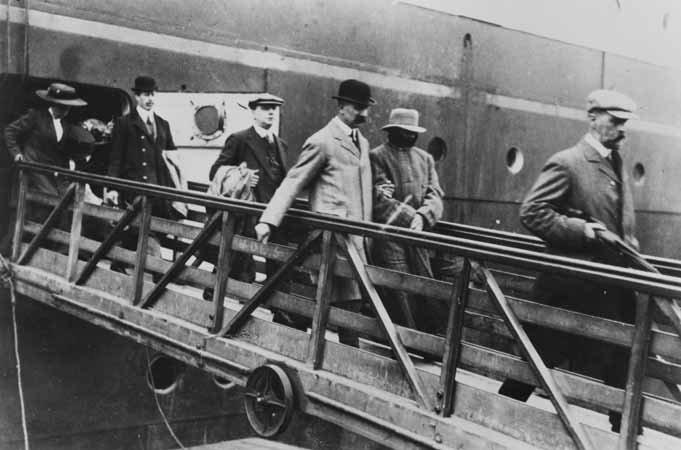

In July 1910, the Laurentic aided in the capture of the suspected murderer Dr. Hawley Harvey Crippen. Chief Inspector Walter Dew of the English Metropolitan police sailed on the Laurentic to overtake and then intercept the SS Montrose which had been instructed to slow down before arriving in Canada.

During the First World War, the Laurentic was commissioned by the Canadian Expeditionary Forces and reclassified as the troop transport ship HMS Laurentic and painted grey.

She was often involved in convoys, one such convoy transported 35,000 Canadian soldiers to Europe in October 1914.

Her captain, John Mathias, was killed on duty on 4 December 1916, when he was accidentally struck by a steel beam whilst attempting to put out a coal fire. He died two days before she reached Liverpool.

The Laurentic departed Liverpool on her final voyage on 23 January 1917 en route to Halifax, Nova Scotia under the command of Captain Reginald Norton. She carried 479 naval officers including naval volunteer reserves and a cargo of gold to be taken to Canada to buy munitions to aid the war effort.

Due to the sickness of four passengers who had developed yellow fever symptoms and required medical assistance, the Laurentic made an unscheduled stop at Buchanan, Ireland to let them disembark.

Once the sick passengers were dropped off, the Laurentic left the port. Captain Norton should have sailed with an escort but he chose to continue without one even in the knowledge that the German U-boat’s were closing in and had been spotted in the area.

Within a couple of hours of leaving the naval base, the Laurentic struck two mines laid by the German submarine U-80. The engine room exploded and the ship lost power without which the pumps could not work and water started to seep in. The ship soon listed 20° making it difficult to lower the lifeboats. The ship sank in less than an hour.

The sea temperature was below freezing, perhaps as cold as -13°C. Many of the survivors who found “safety” in the boats, perished in the lifeboat literally, they were freezing to death. Only 121 passengers survived out of the 475 on board. 354 souls lost their lives.

The captain survived and an inquest was held on 31 January 1917.

News report following Inquest held on 31 January 1917

The New York Times published the following article on 1 February 1917.

LOSS ON LAURENTIC IS NOW PUT AT 350

Captain of Vessel Tells Story of Wreck at Coroner's Inquest - Only 120 Were Saved

MANY DIED IN LIFEBOATS

Admiralty Explains That Cold Weather and Rough Sea Prevented Them from Reaching Shore

LONDON, Jan. 31 - There was ample time to save all on board the British auxiliary cruiser the Laurentic, which was sunk by a mine off the north coast of Ireland last Thursday, says an official statement issued today contradicting reports to the contrary. The fatalities were due to severe weather preventing some in the boats reaching shore. The statement adds:

“A statement appeared in some of the morning papers,” says the official announcement, “to the effect that there was not sufficient time to save all who had escaped being killed by the explosion, and that the ship Laurentic went down carrying with her more than 200 men.”

This is wholly incorrect. There was ample time to save everybody, and the ship was very carefully searched above and below and all hands were put into boats. Those who were lost were lost owing to the cold and the severity of the weather preventing them from reaching shore. Captain R. A. Norton, who was in command of the Laurentic, told the story of the loss of the ship at the Coroner's inquest today over the bodies of seventy-four men of the crew, held at an unnamed city. He said:

“The vessel left port at 5 o'clock on the afternoon of Jan. 25 carrying a complement of 470. At 5:55 I was on the bridge when a violent explosion occurred abreast the foremast on the port side, followed twenty seconds later by a similar explosion abreast the engine room on the port side. Nothing was seen in the water prior to the explosion. The ship was steaming at full speed ahead. No lights were showing.

I ordered full speed astern, fired a rocket, gave the order to turn out the boats, and tried to send a wireless call for help, but found that the second explosion had stopped the dynamo.”

The Coroner asked how many survivors there were.

“One hundred and twenty,” Captain Norton replied. “To the best of my knowledge, all the men got safely into the boats. The best of order prevailed after the explosion. The officers and men lived up to the best traditions of the navy.

At about forty-five minutes after the explosion, prior to leaving the ship, I went around the vessel below with an electric torch and satisfied myself that there were no more men in the ship. The vessel was then very low in the water. When at last I entered a waiting lifeboat bumping dangerously alongside, the ship was sinking, but owing to the darkness and rough weather, we did not actually see her sink.”

“Were there any people killed on board?” asked the Coroner.

“Possibly some were killed in the engine room, but I have been unable to ascertain that, owing to the fact that no survivors are left of the men on watch. I know that all the men got up from the stokehold. The deaths were all due to exposure, owing to the coldness of the night. My own boat was almost full of water when we were picked up by a trawler the next morning, but all the men in the boat survived.

Another boat, picked up at 3 o'clock in the afternoon, contained five survivors and fifteen frozen bodies. They had been exposed to the bitter cold for over twenty hours.”

In reply to questions, Captain Norton said that trawlers arrived within two hours after his signals had been given. No one was asleep on the boat, he added, and there was plenty of time, but some men did not wait to don proper attire.

“Naturally, I was the last to leave the ship,” said the captain in reply to another question.

What happened to the secret cargo? The Laurentic was carrying about 3211 bars of gold or 43 tons of gold worth £5 million in 1908 (£390 million in 2016).

Such a loss of gold was a terrible financial blow for the British government. The gold was greatly needed to fund the effort to the war. Commander Guybon Damont was given the task of trying to retrieve as much gold as possible from the Laurentic. He was an experienced diver. He thought it would take a couple of months to finish the task. He did not know the area and how the sea and weather conditions could change dramatically in such a short space of time with no warning.

It was found that Laurentic was virtually intact laying at an angle of 60° on her port side, 132 feet below the surface. Damont had dived deeper than 200m previously. Divers were given targeted areas to search the gold. The first diver, Dusty Millar located the cargo hold where the gold was kept. He was the only driver to see all the gold. He dived several times and retrieved over £80,000 worth of gold. Weather conditions deteriorated and salvage had to stop.

Between 1917 and 1924, over 5000 dives were made.

In 1924, the British government abandoned the salvage operation because it was not financially viable. The gold had been recovered except for 25 bars of gold. Bounty was paid to the salvage team of two shillings and sixpence (12½p every £100 recovered). Eight team members got the MBE.

In the 1930s, three more gold bars were discovered by private British salvage company. In the 1960s, salvage rights were bought by the Cossum brothers, but no gold was ever found. 22 gold bars are still unaccounted for to this day.

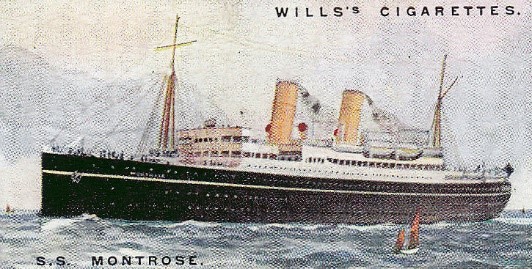

RMS Megantic

The Megantic was built by Harland and Wolff under keel number 399. She was launched on 10 December 1908 and completed on 3 June 1909. She was 550.4 feet long with a beam of 67.3 feet and had a gross tonnage of 14,878. She had three decks and two partial decks. She could maintain an average speed of 16.5 knots.

The Megantic (formally the Albony), commenced her maiden voyage on 17 June 1909. She served the Liverpool to Canada route. On 31 July 1910, Dr Crippen returned to England for his trial for murder on the Megantic, after he was arrested in Canada.

After the war, Megantic had a refit in 1919 and her First Class accommodation was increased. She carried on being a passenger liner until the last passage in May 1931. She was sold for scrap in 1933.

“Olympic Class” liners

On 7 June 1906, the Cunard Line launched the I. She had a gross tonnage of 31,550. She had nine decks and 25 boilers installed. She could maintain speed of at least 25 knots. She could carry over 2000 passengers. Cunard was able to build such a ship due to government subsidised funding. The coming of such Cunard vessels spurred the WSL to construct even bigger and better liners of its own.

Joseph Bruce Ismay and Lord William James Pirrie wanted to build ships even bigger than the Lusitania and the Mauretania. The two gentlemen planned to build the largest man-made moving objects on earth; and soon referred to as the “Olympic class” liners.

The company, with the aid of the chief designer at Harland and Wolff, the Honourable Alexander Carlisle (Pirrie’s brother-in-law) put plans to motion. For safety, Carlisle wanted 64 lifeboats on board but the owners considered this extravagant. After several rethinks only 16 were provided. The keel of the RMS Olympic, the first “Olympic class” was laid on 16 December 1908. See also the history of the RMS Titanic.