The History of the Cunard Line from 1906

RMS Mauretania (1906)

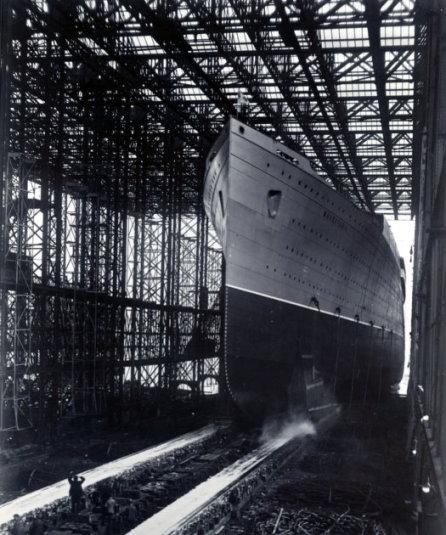

The hull of the Mauretania was laid on 18 August 1904 and was launched on on 20 September 1906 by the Duchess of Roxburghe. She was 790 feet long with a beam of 88 feet and had a gross tonnage of 31,938.

See RMS Lusitania for more detials about specifications and interiors

The Mauretania and Lusitania both came into service in 1907.

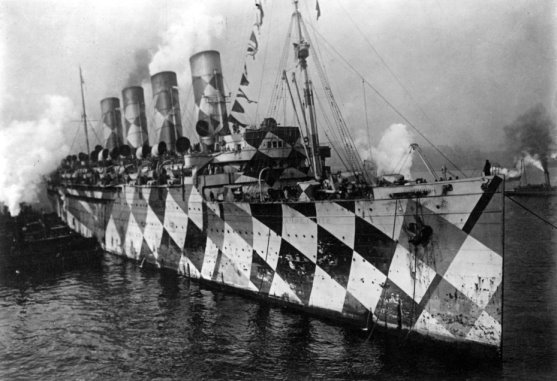

The Mauretania took 29 months to construct and Atlantic speed records quickly fell to her. The Mauretania set the unbeaten record for 22 years by averaging over 26 knots on a round voyage. One competitive reaction was to aim at size rather than speed, and as the short Edwardian period was ending, it brought to the Atlantic ships which could be described as “slow super liners.” Cunard responded by building the Aquitania. She exceeded the Mauretania in size by 15,000 tons and carried an additional 1,000 passengers. She did not seek to match her speed.

In 1917, Cunard’s new headquarters at Liverpool’s Pier Head were completed. The building was designed in Italian Renaissance style and had several friezes along its outer elevations. The Pier Head elevation featured the coat of arms of Britain’s allies during the First World War.

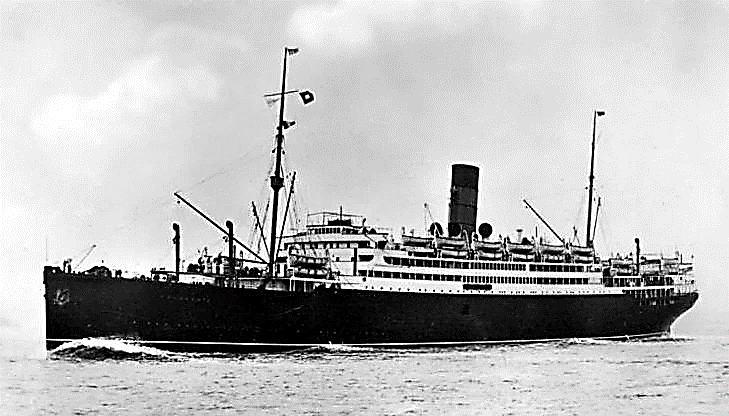

RMS Franconia (1922)

Cunard was ready to restore a commercial fleet, an onerous task considering the condition of imbalance caused by war losses, and by the allocation of German tonnage by way of reparations. Nine of Cunard’s fleet had been lost between 1914 and 1918. Cunard commissioned five 20,000 ton ships: the Scythia (no. 2), the Samaria, the Laconia (no. 2), the Franconia (no. 2) and the Carinthia together with six 14,000 ton ships to replace those lost during the war. The ships would serve as cruise ships.

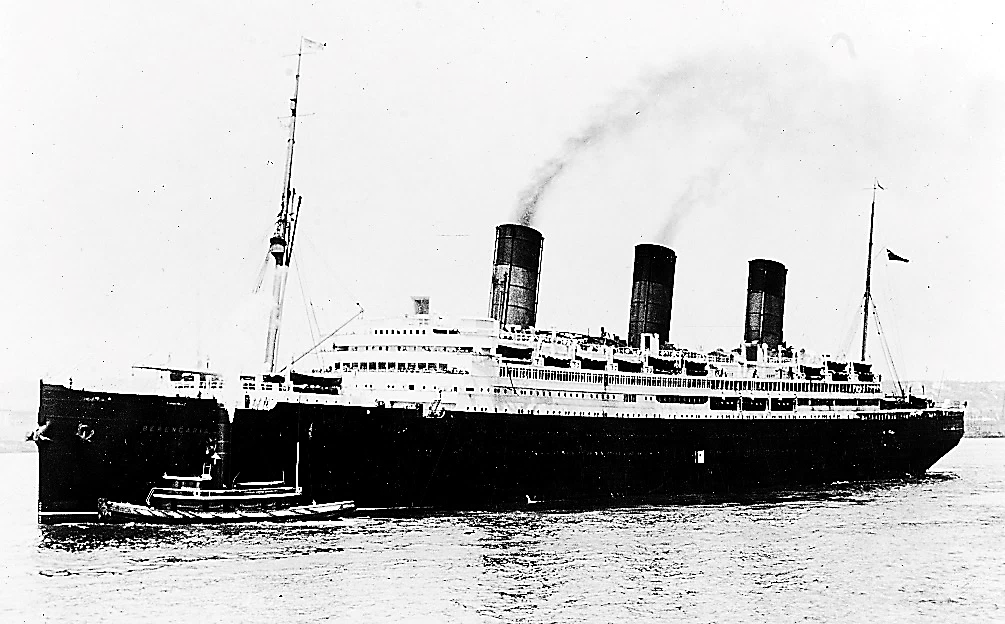

Cunard had the Mauretania, the Aquitania, and half the ownership of the Imperator, renamed Berengaria, one of the German monster ships of over 50,000 tons. The Bismarck passed to the WSL and renamed the Majestic (No 2), again on the basis of a 50% share with Cunard. The arrangement was clumsy and was soon abandoned. Instead, each company accepted the responsibility for one ship. With these three ships, Cunard was in a strong position to maintain its express service from Southampton to New York. Five main Atlantic routes were serviced including a new venture between Hamburg and New York.

In 1922, a new service from Liverpool to Canada began with the Albania and was quickly developed when the Carmania and Caronia joined her.

The "Queens" Project

The Mauretania, Aquitania and Berengaria would become outclassed by the early thirties. A period of intense economic nationalism set in; the Atlantic had become a prestige route. There were also changes in travelling habits. Holidays in America or in Europe were no longer confined to the wealthy; with affordable fares in Second and Third Class, the idea of pleasure cruising took hold.

Innovations of this kind meant better utilisation of tonnage, and winter cruising in particular, when Atlantic traffic was lower, produced useful alternative revenues.

Future designs of ships had to embrace the latest technical advancements. Such construction would come at a huge cost. A super-liner could cost up¬wards of £5 million, a considerable sum in the 1920s. Cunard envisaged that a financially feasible weekly express service between Southampton and New York was only possible with two ships: the Queen Mary and the Queen Elizabeth. Every week in the year (with the exception only of overhaul periods) one ship would leave Southampton, the other New York. To achieve this, the guaranteed service speed had to be 28 knots.

An irony of the Queen Mary's beginning, was the coincidence of a world economic slump. Construction work was halted on the Queen Mary in December 1931. For 27 months she lay on the stocks at Clydebank. During this whole period, foreign nations were going ahead with Atlantic super-liners, most of them subsidised.

A weekly service could be operated from Southampton. The ports east of Cherbourg, for example, Hamburg and Bremerhaven, were not practical bases. Therefore, Cunard was in the enviable posi¬tion of being able to operate a weekly service but could not because of the depletion of funds following the Bill Market Failure of 1931.

The Queens were not conceived as prestige ships. The prime reason for their building was summed up by the Cunard Line’s Chairman, Sir Percy Elly Bates, in a paradox:

“So far from attempting to construct steamers simply to compete with others in size or speed, the Cunard Company is projecting a pair of steamers which though they will be very large and fast, are in fact the smallest and slowest which can fulfil properly all the essential economic conditions. To go beyond these conditions would be extravagant; to fall below them would be incompetent, as the Company would be simply leaving to others a direct invitation to compete with it on more economic terms.”

Merger with White Star Line

In 1933, the King George V Graving Dock, built for the RMS Queen Mary, by Southern Railways at Southampton was opened. In the same year, Neville Chamberlain asked Lord William Douglas Weir, 1st Viscount Weir, to produce an assessment of the British position on the north Atlantic passenger routes. He wanted to see an end to the wasteful competition which existed between the Cunard Line and the WSL. A condition of the Government loan which made it pos¬sible to complete the Queen Mary, and finance the Queen Elizabeth, was a merger between the two companies.

In 1934, Cunard and WSL merged as the Cunard-White Star Line Limited. Work was resumed on the Queen Mary and with it, the morale of the shipbuilding and shipping industries was restored. By the time of her completion in 1936, the building programmes of foreign competitive companies had been completed, with the commissioning of such ships as the French Line's 83,000 ton SS Normandie, the Italian Line's Rex and Conte di Savoia, and earlier the German 50,000 tonners Bremen and Europa.