Famous Passengers and Crew of the RMS Titanic

This section is a small biography of famous people associated with the Titanic.

Captain Edward John Smith, R.D, R.N.R. (1850-1912)

Captain EJ Smith was born on 27 January 1850. His parents were Edward and Catherine Smith. They lived in Hanley, Stoke on Trent, England. He attended Etruria Country Primary School.

In 1867, at the age of 17, he began an apprenticeship on the clipper ship Senator Weber, with the sailing firm of Andrew Gibson & Co in Liverpool. He gained his Second Mate's Certificate on 12 August 1871 and his First Mate's Certificate on 8 April 1873. Smith finally gained his Master's Ordinary Certificate on 26 May, 1875, at the age of 25. He was given his first command of the 1040 ton sailing ship, the Lizzie Fennell, in 1876. He spent the next couple of years transporting cotton and assorted goods to Britain from southern U.S. ports such as Savannah and Galveston.

His career with the WSL began in March 1880. He was appointed as the fourth officer on the Celtic. His progression up the ladder was fast and exemplary.

In 1887, Captain Smith received his first WSL command, the Republic.

In 1888, he joined the Royal Naval Reserve as a full Lieutenant because he had a Master's Certificate and he could use the designated letters R.N.R. after his name. He could also fly the Blue Ensign on any merchant vessel that he commanded under warrant number 690.

He married Sarah Eleanor Pennington and had one daughter Helen Melville Smith. Helen was born in 1898.

In 1895, Captain Smith was given command of the Majestic and remained her captain for nine years. During the Boer War (1899-1902), the Majestic transported troops to South Africa. In 1903, Captain Smith was awarded the Transport Medal showing the South Africa clasp.

By the turn of the Century, the WSL awarded him the command of their greatest ships. His yearly salary of £1250 made him the highest paid captain on the sea. In 1904, he was given command of the world’s largest ship: the Baltic.

On 29 June 1904, the Baltic sailed from Liverpool to New York without incident. After three years commanding the Baltic, Captain Smith was given command of the Adriatic. The maiden voyage went without incident.

During his command of the Adriatic, Smith received the Royal Naval Reserve's “Long Service” medal as well as a promotion to Commander. He would now sign his name “Commander Edward John Smith, R.D., R.N.R.” with “R.D.” meaning “Reserve Decoration.” He had two medals which later photographs show him wearing them (pictured above).

Following the launch of the Olympic, Captain Smith was the obvious choice for commander. From May 1911 until March 1912, he would again command the world’s biggest ship.

All the commands which Captain Smith had undertaken had run smoothly without incident until 20 September 1911 when the Olympic collided with the HMS Hawke. The subsequent inquiry into the accident found that it was caused by the suction from the Olympic’s propellers pulling the Hawke into her side. Financially it was a disaster for the WSL. The hull and propeller were severely damaged so the Titanic’s propellers were used as replacements, thus the completion of the Titanic was delayed at a great cost to the WSL.

Following repairs, the Olympic returned to service but in February 1912, she lost a propeller blade and had to return to her builder for emergency repairs. To get her back to service quickly, Harland and Wolff had again to pull resources from the Titanic so delaying her maiden voyage from 20 March until 10 April. The incidents had dented Captain Smith’s unblemished record of achievement.

Perhaps he spoke too soon when he stated on 16 May 1907 that, “I [have] never seen a wreck and have never wrecked, nor was I ever in any predicament that threatened to end in disaster of any sort.” Not only had the Olympic collided with the Hawke, many lives would be lost with the foundering of the Titanic (although Captain Smith was not entirely to blame) five years later.

From 1 April 1912, Captain Smith took command of the Titanic and over saw her trials. He took with him, Chief Officer Henry Wilde from the Olympic which caused some resentment amongst other of the Titanic Officers. Hopefuls like Murdoch and Lightoller were demoted to First and Second Officers. Second Officer Blair left the Titanic’s company altogether.

Captain Smith followed a routine. Each morning at 10 a.m., he would meet with department heads and take their reports. By 10.30 a.m., he would be ready, complete in full uniform to tour the ship from the First Class Dining room to the engine rooms.

When, the Titanic struck an iceberg at 11.40 p.m. on 14 April 1912, Captain Smith was off duty asleep in his cabin. He awoke to the sound of engines stopping. First Officer Murdoch was on watch on the bridge. Captain Smith joined Murdoch and was given the report. He consulted Thomas Andrews who carried out a site investigation and calculated the life expectancy of the doomed liner. Captain Smith ordered the wireless operators to send the CQD signal of distress and ordered the rockets to be fired.

How Captain Smith met his end is unknown. Some accounts (the most credible) witnessed Smith returning to the bridge moments before it was submerged to down with his ship. Other accounts say he was thrown from the ship and seen rescuing a child and then returning to the ship. Other accounts tell Captain Smith shot himself.

There are many memorials dedicated to Captain Smith. At Litchfield, there is a larger than life bronze statue of him which was unveiled by his daughter on 29 July 1914 (pictured below).

Charles Herbert Lightoller (1874-1952)

Charles Lightoller was born on 30 March 1874, in Chorley, Lancashire, England. His family owned a cotton mill and so he came from a relatively wealthy background.

Charles Lightoller was born on 30 March 1874, in Chorley, Lancashire, England. His family owned a cotton mill and so he came from a relatively wealthy background.

By his thirteenth birthday (February 1888), he had already began his four year apprenticeship on board the Primrose Hill. The next five years would be dramatic. Following that voyage, he sailed on the Holt Hill. During a storm, the Holt Hill was badly damaged and had to call in at Rio de Janeiro for repairs. Unfortunately, it was a time of revolution, uprising and even worse, a time of small pox epidemic. On 13 November 1889, a storm demasted the Holt Hill and the ship ran aground on the small Island of Ile Saint Paul. Fortunately, all the crew of the Holt Hill were rescued and Lightoller returned to England on the Duke of Abercorn. Lightoller was a very determined seafarer. His past experiences could have extinguished his enthusiasm but his confidence soared.

His third voyage on the Primrose Hill took him to Calcutta. With his valuable experience, he secured his Second Mate’s Certificate. At the age of 21, he joined Elder Dempster’s African Royal Mail Service and was introduced to steamships. He spent 3 years travelling the West African coast where he contracted malaria and nearly died.

To recuperate, he left sea life for a couple of years and in January 1900, he joined the WSL.

His first commission was on board the Medic as Fourth Officer. The Medic’s route from England rounded the Cape en-route to Australia. On one voyage, he met his bride to be, Sylvia Hawley-Wilson. Most of Lightoller’s early career with the WSL was served on the Majestic under the command of Captain Smith. Lightoller went on to serve as the Third Officer on Oceanic.

In 1907, the Lightoller family moved from Liverpool to Southampton soon after the Oceanic was transferred to Southampton. For a time, Lightoller was promoted to First Officer.

During the Titanic’s trials, Lightoller acted as First Officer however, Captain Smith appointed Henry Wilde from the Olympic to be Chief Officer for Titanic’s maiden voyage. This meant that the Titanic’s Chief Officer Murdoch became the First Officer and Lightoller became the Second Officer.

Lightoller’s role in the Titanic disaster

On 14 April 1912 at 10 p.m., Lightoller was relieved from his post on the bridge by Chief Officer Murdoch who had instructed the lookouts to keep a close vigil for ice. Lightoller retired to his cabin when at 11.40 p.m., felt the collision with the iceberg. By 11.50 p.m., Fourth Officer Boxhall informed Lightoller the damage was serious and that was water was flooding into the mail room.

Lightoller’s task was to evacuate passengers in the even numbered lifeboats and he tried rigidly to enforce the “women and children first” rule.

By 2.00 a.m., all of the Titanic lifeboats had been lowered. Only four collapsible Engelhard boats remained. Collapsible A and B were lashed upside down on the roof of the Officer’s Quarters. As Collapsible D was only loaded with 15 women, Lightoller allowed men into the boat to fill it. 47 people were in the boat.

Lightoller refused to go in the collapsible when invited by Chief Officer Wilde. Lightoller tried to release Collapsible B but as the Titanic lunged forward, he was swept into the sea. For a short time he was sucked under the water but as the boilers blew he was catapulted to the surface alongside Collapsible B. He swam to it and held on to a rope at the front. The forward funnel broke free and hit the water which washed the collapsible further away from the sinking ship.

He managed to save about 30 men on the upturned collapsible B, amongst whom were Harold Bride and Colonel Archibald Gracie.

During the Carpathia rescue, Lightoller was transferred into lifeboat 12 which although overcrowded, kept afloat and was the last boat to be rescued.

Upon arrival in New York, Lightoller testified at the American Inquiry where he defended the honour of Captain Smith and the WSL.

Following the disaster and subsequent inquiries, Lightoller returned to sea as First Officer on the Oceanic. During the First World War, the Oceanic became the HMS Oceanic, an armed merchant cruiser with Lightoller appointed as Lieutenant in the Royal Navy. HMS Oceanic was assigned to Northern Patrol but was too big to charter these waters. On 8 September 1914, she ran aground near the Island of Foula, broke up and was lost.

Lightoller’s next assignment was on the Campania after conversion to a sea plane carrier. Lightoller became an observer in a short 184 sea plane.

By the end of 1918, Lightoller became a full Commander and returned to the WSL as Chief Officer on the Celtic.

After a 20 year career with the WSL, he reluctantly retired. It appeared to him that due promotion was withheld because of widespread passenger reluctance to sail on a ship commanded by one of the Titanic’s former officers. Lightoller was dismayed that he did not become a First Officer of the highly successful Olympic.

In 1935, he published his autobiography, “Titanic and other Ships.” His wife had been insisting that he wrote it for many years especially after the Titanic disaster and the stigma attached. The dedication in the book reads “[to my] persistent wife, who made me do it.”

In his retirement, Lightoller purchased the Sundowner. On 31 May 1940, at the age of 66, he was asked by the Admiralty to surrender his vessel to aid in a rescue mission at Dunkirk. Lightoller would not let the Admiralty take control of his ship unless he and his eldest son Roger were behind the wheel. On the beach at Dunkirk, Lightoller managed to squeeze 130 men into the Sundowner.

By the age of 72, Lightoller had retired for good except for running a peaceful boatyard called Richmond Slipways where he built motor launches for the London River Police.

He died On 8 December 1952, and was cremated at Mortlake Crematorium, Richmond upon Thames, England.

The “Unsinkable” Margaret (“Molly”) Brown (1867-1932)

Margaret Brown was born on the 18 July 1867. Her parents were Irish immigrants John and Johanna Collins. She was born in Hannibal, Missouri.

Margaret was educated at the local grammar school run by her Aunt, Mary O’Leary.

In her teens, she worked at Garth’s Tobacco Company in Hannibal but at the age of 18, moved to Colorado where her sister and brother-in-law had set up a blacksmith shop.

Margaret Brown was born on the 18 July 1867. Her parents were Irish immigrants John and Johanna Collins. She was born in Hannibal, Missouri.

Margaret was educated at the local grammar school run by her Aunt, Mary O’Leary.

In her teens, she worked at Garth’s Tobacco Company in Hannibal but at the age of 18, moved to Colorado where her sister and brother-in-law had set up a blacksmith shop.

Margaret commenced work for May-Daniels and Fisher Mercantile in Leadville, in the carpets and draperies department. In 1886, Margaret met and married James Joseph Brown, a miner and had two children, Lawrence and Catherine. Soon after their births she became involved in the feminist movement in Leadville; “The Colorado Chapter of the National American Women’s Suffrage Association.”

By 1893, Brown’s mine had become very successful especially after he struck gold. He became one of the most successful mining men in the country. When the Titanic was due to sail on her maiden voyage, Margaret received word, whilst staying with the John Jacob Astor party, that her son Lawrence was ill, and decided to return to America via New York. She booked the first available sailing across from Southampton to New York: on the Titanic. Catherine remained in London.

Whilst the Titanic was sinking, Margaret was assisted into lifeboat No. 6. There should have been 65 passengers in the boat but there were only 21 women, 2 men and a 12 year old boy. It is a good example of the lifeboats sailing away less than half filled. Once the boat was lowered and touched the water she assisted in the rowing.

Margaret demanded that the boat should be turned around to pick up survivors from the freezing water. Quartermaster Robert Hichens ordered the women to continue rowing in the opposite direction away from the disaster site. He argued that if they picked up survivors, there would be so much panic that they might inadvertently overturn the boat resulting in another 24 deaths.

Once on board the Carpathia, her role in the disaster did not end. She searched the ship for blankets and supplies and gave comfort to the survivors. Remarkably, she rallied the First Class passengers to donate money to help the less fortunate passengers. $10,000 was raised before the Carpathia reached New York. She remained in New York and became President of the Survivors Committee. She had earned the nickname “The Unsinkable Mrs Brown” (the name “Molly” was introduced by Hollywood in subsequent films – presumably a marketing exercise?)

On 29 May 1912, Margaret presented a silver cup and gold medal to Captain Rostron of the Carpathia and a medal to each crew member. She also helped to erect the Titanic Memorial in Washington DC.

She continued to fight for women’s rights and labour issues. In 1932, she was awarded the “French Legion of Honour” for work she carried out during the First Word War.

Her husband died in New York in 1922 and gradually her finances slipped away. Margaret died on 26 October 1932 from a brain tumour. She was a very remarkable character.

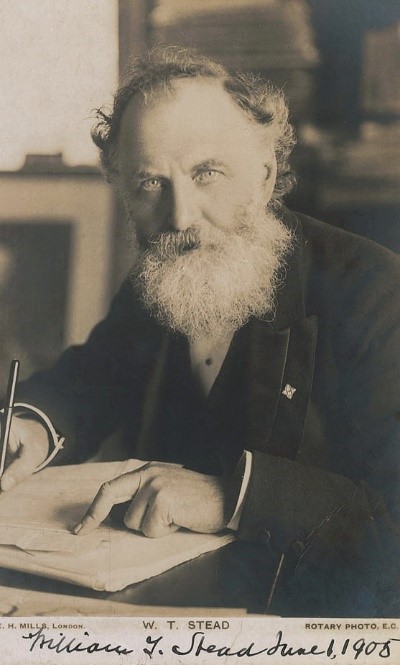

William Thomas Stead (1849-1912)

William Stead was born on 5 July 1849, the son of Reverend W. Stead and Isabella Stead. They lived in Manse, Embleton, Northumbria, England. Initially, Stead was educated by his father but further educated at Silcoates School near Wakefield. At the age of 14, he was an apprentice to a merchant’s counting house on the Quayside in Newcastle upon Tyne.

He had developed a passion for writing and by 1870 had begun to contribute towards articles in the newly formed Northern Echo in Darlington. His work was admired so much so that he became editor in 1871.

During the nine years with the Northern Echo, he met and married Emma Lucy Wilson and had 6 children. Looking for career progression, Stead and his family moved to London to become the assistant editor of the Pall Mall Gazette in 1880. Before long, Stead took over John Morley’s position as editor. He remained there for seven years.

Some of his editorials were so influential they prompted governments to act or to rethink policies. For example, his article called “Truth about the Navy,” lead to governmental increased subsidy.

In 1885, Stead started a crusade against child prostitution and published a series of articles “The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon.” The campaign was so successful that the Criminal Law Amendment Act increased the age of sexual consent to 16 years. The story opened respectable society's eyes to the world of London vice. Stead was shocked to find that the government knew of the problem but had turned a blind eye to protect the trade's wealthy clientele. Stead himself became the new law's first victim. As part of his exposé, he had staged the purchase of a girl called Eliza Armstrong (Lily in the PMG) in an ill-conceived attempt to show how easily such impoverished victims could be acquired.

His actions left him open to prosecution and he was subsequently sentenced to three months in prison for abduction and indecent assault. He was convicted on grounds that he had failed to first secure permission for the “purchase” from the father of the girl.

In 1886, he started a campaign against Sir Charles Dilke, 2nd Baronet, over his nominal exoneration in the Crawford scandal. The campaign ultimately contributed to Dilke's misguided attempt to clear his name and consequent ruin. Stead left the Pall Mall Gazette and established several monthly publications, most notably the “Review of Reviews.” From around 1890, he became involved in Spiritualism and started to preach about “Peace through Arbitration.”

Years before Stead travelled on the Titanic he had had premonitions about the fate of the liner (see Chapter 11). Nevertheless, Stead purchased a ticket for passageway on board the Titanic. He was going to a Peace Congress meeting at Carnegie Hall on 21 April 1912. On the evening of 13 April, he met a number of people in the First Class Smoking Room and began to tell ghost stories, one being the Mummy’s Curse, see The “Titanic Curse.”

Joseph Bruce Ismay (1832-1937)

Joseph Bruce Ismay was born in Crosby (Liverpool) on 12 December 1862. He was the eldest son of Thomas Henry Ismay and Margaret Bruce. His father was senior partner of Ismay, Imrie & Co, founder of the WSL.

J. Bruce Ismay was educated at Elstree School and at Harrow. He studied for a further year in France until old enough for a four year apprenticeship in his father’s company.

He married Julia Florence Schieffelin and had two sons and two daughters.

His father died in 1899 and so Bruce took over the family business. The firm went from strength to strength, so much so, that it was approached by an American company to merge assets and companies. As a result International Mercantile Marine Company was formed.

Ismay met with Lord Pirrie, Chairman of Harland and Wolff shipbuilders. The topic of conversation was the Lusitania and the Mauretania. Both were owned by their rival company, Cunard. Ismay raised the concept of bigger and more luxurious ships in order to surpass this competition. The ships would be the biggest ships afloat and the most luxurious: the “Olympic class” liners.

Ismay generally sailed on his ships during their maiden voyage, the Titanic being no exception. When the I hit the iceberg, Ismay made his escape in Lifeboat C. Many said that he should have gone down with the ship in the knowledge that it was under his encouragement that the ship should cross the Atlantic as fast as possible. Ismay was “showing off” his new vessel to the world.

Despite ice warnings, the I crossed the ice field at 22½ knots. One wonders if Captain Smith was ordered or perhaps suggested to maintain speed by the “owner” of the WSL and hence ignore ice warnings or at least to underestimate them.

Some witnesses stated that Ismay was dressed as a woman, to avoid attention as he climbed into the lifeboat. It is very doubtful that he would have gone to such lengths. His position within the WSL would have allowed him to slip into the boat unquestioned by the officers of the Titanic.

Whatever Ismay did, or how he did it, does not alter that fact that there were women and children still on the ship. He should have given up his place for one of and was subsequently nicknamed “J. Brute Ismay.”

Following his rescue, he became a crucial witness in the aftermath Inquiries.

After the Titanic disaster, he continued to work within the nautical sector and inaugurated a cadet ship called the Mersey used to train officers for the merchant navy. He donated £11,000 to start a fund for lost seamen, and in 1919 gave £25,000 to set up a fund to recognize the contribution of merchant mariners in the First World War.

J. Bruce Ismay died on October 17, 1937 of a cerebral thrombosis. He is buried in Putney Vale Cemetery in London.

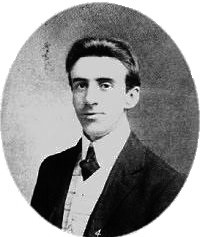

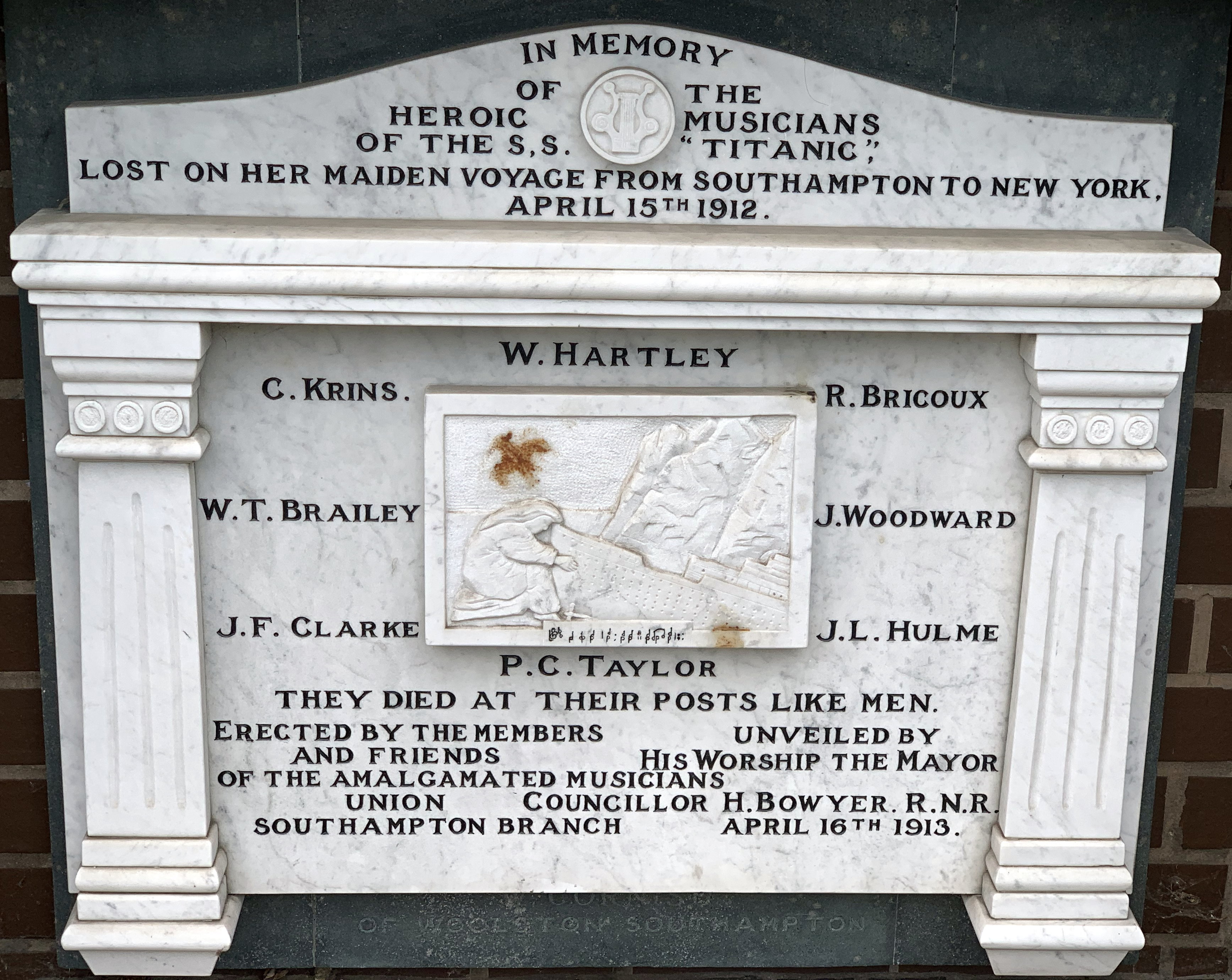

Wallace Hartley (1878-1912) and Titanic’s Orchestra

Wallace Henry Hartley was born on 2 June 1878. He was raised in Colne, Lancashire, England where his father, Albion Hartley, was the Choirmaster and Sunday School Superintendent at Bethel Independent Methodist Chapel. Wallace studied at Colne's Methodist Day School and was taught how to play the violin by a fellow congregation member.

He left the family home in 1903, to live in Bridlington and he joined the municipal orchestra. He later moved to Dewsbury, West Yorkshire and in 1909, he joined the Cunard Line as a musician, serving on the ocean liners Lucania, Lusitania and Mauretania1.

The music agency C.W. & F.N. Black supplied musicians for Cunard and the WSL. When Hartley was serving on the Mauretania1, he was transferred to the music agency. Such a transfer meant that his status on board changed from being a crewmember to passenger. He started service on the Titanic as bandleader.

The Titanic’s Orchestra

Name |

Position |

Age |

Hometown |

Quintet |

Violinist |

33 |

Colne, Lancashire, England |

John Frederick Preston Clarke |

Bassist |

30 |

Liverpool, Lancashire, England |

John Law Hume |

Violinist |

21 |

Dumfries, Scotland |

John Wesley Woodward |

Cellist |

32 |

Oxford, England |

Percy Cornelius Taylor |

Pianist |

32 |

London, England |

Trio |

Cellist |

20 |

Cosne-sur-Loire, France |

Theodore Ronald Brailey |

Pianist |

24 |

London, England |

Georges Alexandre Krins |

Violinist |

23 |

London, England |

What did the band play during dinner?

The orchestra was divided into two sections - a quintet and a trio. Hartley led a quintet and played at teatime, after-dinner concerts, and Sunday services, among other occasions.

The trio consisted of a violin, cello and piano played by Roger Bricoux, George Krins and Theodore Brailey. They played in the À La Carte Restaurant and the Café Parisien.

The ship’s orchestra wore blue tuxedos during dinner performances. They had a varied repertoire and would have played requests as given. Some of the music would have included famous compositions such as The Barber of Seville, Rossini; Aida, Verdi; Madam Butterfly, Puccini; The Mikado, Gilbert & Sullivan; Waltzes by Strauss and many more.

His role during the final hours of Titanic

Soon after Thomas Andrews had calculated that the ship would sink as a mathematical certainty, panic took hold. Wallace Hartley and his eight-man orchestra played a crucial part in reducing the tension during the final hour and a half before the Titanic foundered.

During the evacuation, the band assembled near the entrance to the Grand Staircase and started to play to sooth the nerves of the First Class passengers who had gathered on the Boat Deck. They played well-known songs until the final moments. There are many accounts as to what they actually played as a final song. It has been suggested that it was the hymn “Nearer, My God, to thee” but “Autumn” was reported to have been played by Harold Bride.

Whichever piece was played, it was the sheer heroism of these men who carried on playing whilst their world came to an end, what is remembered today. Their courage and devotion helped to calm the tension as the stranded passengers foresaw their impeding fate.

All of the band members went down with the ship. Hartley’s body was recovered two weeks after the sinking.

His body was transported to England by the Arabic and returned to Colne under the direction of his father. A funeral was held on 18 May 1912 with over 30,000 on seers of the procession. Over 1000 people attended the funeral. A memorial bust was erected outside the town library in 1915.

On 19 October 2013, Henry Aldridge & Son in Devizes, Wiltshire England auctioned a violin owned by Wallace Hartley for £900,000.

Stanley Philip Lord was born on 13 September 1877 at Bolton, Lancaster, England.

At the time of the Titanic disaster, he was captain of the SS Californian. The ship was in the vicinity of the Titanic but did not go to the rescue.

Lord began his sea training when he was 13 years old. With the relevant experience and learning, he obtained his Second Mate’s Certificate in February 1901 and then obtained his Master’s Certificate. The Extra Master’s Certificate was awarded to him shortly afterwards. He served as second officer in the barque Lurlei.

He joined the Californian of the Leyland Line in 1911.

On 5 April 1912, the Californian sailed from London to Boston. The ship ran into the ice and Lord ordered the ship to “stop engines” at 10.21 p.m. on 14 April 1912.

At the time of the Titanic struck the iceberg, the Californian was stationary but close: within 20 miles. After the collision, the Titanic crew fired distress rockets. They were seen by the officers and crew of the Californian. Captain Lord was asleep after a 17 hour watch. He was woken twice by his crew who informed him about the rockets. He told his crew that they were probably “company rockets” fired as a means to identify themselves to other boats.

Once the Titanic had sunk, the crew of the Californian thought that the liner had just steamed away.

Shortly after 5.00 a.m., Captain Lord received a wireless from the Frankfurt that the Titanic had sunk and hearing the news joined in the search for bodies/survivors alongside the Carpathia.

Inquests were held into the sinking by the British Board of Trade and the Americans. Captain Lord gave his testimony in both. Captain Lord was heavily criticised for his actions but no charges were brought against him. At the inquiries he was not permitted to defend himself.

It was reported by the Washington Herald on Saturday, 17 August 1912, that “Captain Lord explained the proceedings on board his ship on the night of the disaster and declared that he hopes to remove an undeserved stigma upon his character.”

The tragic events of the sinking of Titanic tormented him until his death in 1962. He had approached the Board of Trade to examine the facts in an effort to clear his name but his petition was rejected.

The British government reappraised the findings in 1988. The Marine Accident Investigation Branch (MAIB) concluded the crew of the Californian had seen the rockets. The report was critical of how the crew reacted to the signals they saw. It was noted that the position reported by the Titanic was wrong and even if the Californian had gone to the rescue they would have arrived at about the same time as the Carpathia.

On 11 April 2012, the BBC reported that Captain Lord had been harshly treated. In the article called “Titanic disaster: How history has judged Bolton's sea captains” written by Jim Clark asked if Lord deserved the blame. He referred to the 1958 film “A Night To Remember” in which Lord is portrayed as the villain. After the film, Lord demanded a new Inquiry to clear his name.

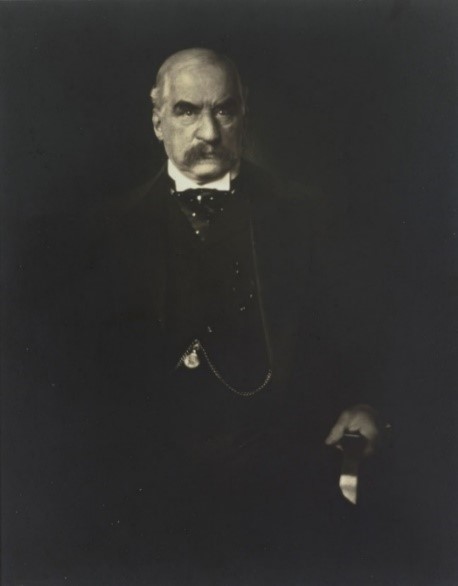

After his death in 1962, the case was taken up by the Bolton East MP, Bow Howarth. “I thought it was worth looking at the evidence again because I just cannot believe that a man of his experience in that environment would have just ignored anything that could have been interpreted as a call for help stop it doesn’t ring true,” he said. John Pierpont Morgan was one of the most powerful bankers of his time. He was born on 17 April 1837 in Harford Connecticut. He graduated from high school in Boston in 1854 and went to Europe to study. He returned to New York in 1857 to start his finance career.

In 1861, he married Amilia Sturgess, the daughter of a very wealthy New York businessman. Amelia died only four months after the wedding from tuberculosis.

In 1871, he partnered the Drexels of Philadelphia and formed the Drexel, Morgan and Co. When Anthony Drexel died in 1895, Morgan renamed the company J.P. Morgan and Co.

In 1865, he married Frances Louisa Tracy and they had four children.

In the late 1800s, Morgan was heavily involved in the reorganising and restructuring of the number of troubled railroads across America. He gained control of significant portions of their stock and eventually controlled a sixth of all America’s rail lines.

In 1895, Morgan was even able to provide financial support to the American government and loaned them more than $60 million.

In 1902, J.P. Morgan and Co financed the IMM. One of the subsidiaries was the WSL. The sinking of the Titanic was a financial disaster for the IMM. In 1915, the IMM was bankrupt.

During the 1907 financial crisis, he helped again. Some officials thought he was getting too powerful. There was a congressional committee investigation chaired by US representative Arsene Pujo. A “money trust” was being investigated and Morgan gave evidence. Soon after the Federal Resource System was created in 1913.

Morgan died while travelling abroad on 31 March 1913. He died in the Grand Hotel in Rome. His estate was worth $68.3 million ($1.39 billion today). He collected great works of art gemstones. His art collection was estimated to be worth $50 million. Harold Lowe was born on 21 November 1882 at Eglwys Rhos, Caernarfonshire, North Wales. He was one of eight children. His ambition was to become a seafarer much to the displeasure of his father, who wanted him to take up an apprenticeship in Liverpool enroute to becoming a prominent Liverpool businessman.

Lowe joined the merchant Navy after he ran away from home when he was 14.

In 1906, he passed his Second Mate’s Certificate and secured his First Mate’s Certificate in 1908.

He was the third officer on the Belgic and Tropic. He was the Fifth Officer on the Titanic.

When the Titanic struck the iceberg, Lowe was off duty, in his cabin after being relieved by Sixth Officer James Moody. The collision woke him and once dressed rushed to offer help.

Third Officer Pitman charged him with lowering Boat No. 5. Moody told Lowe that he should go to lifeboat No. 14 where a group of frightened men had gathered and had become rowdy. In order to restore order, Lowe fired his revolver three times in the air.

Once lifeboat No. 14 had been rowed to safety, Lowe returned to the scene to pick up survivors from the icy cold waters. He gathered together several lifeboats so that passengers could be redistributed. Lowe took an empty lifeboat and picked up four men during his search. Later, his boat and the other lifeboats huddled together, were picked up by the Carpathia.

On 19 April 1912, it was reported in the Worcester Gazette that Lena Rogers of Boston was saved from the Titanic in a boat which carried 55 women passengers.

“As we left the Titanic, several men were on the point of jumping into our boat, already overcrowded. They were stopped by Officer Lowe drawing a revolver. After taking us out of the range of the Titanic's suction, he transferred us to other boats that had not been completely filled and went back for more from the sinking ship. Too much praise cannot be given the officer for his work. We were in the boat for three or four hours listening to the cries and groans of those who had jumped overboard and were not rescued, and those in other boats. She also described the lifeboat as being “crowded to more than its capacity.”

The Carpathia arrived in New York on 18 April 1912 at Pier 54. Lowe returned to England on the Adriatic. He gave testimony in both British and American inquiries. Lowe gave a thorough description of the disaster and the events of the night. He was hailed a hero in his hometown of Barmouth in North Wales and a reception was held in his honour at which over 1300 people attended.

The remainder of his career was served at sea in the Royal Naval Reserve during the First World War after which he returned to service with the WSL.

He died on 12 May 1944. He is buried at Churchyard in Rhos-on-Sea. Sir Cosmo Edmund Duff-Gordon was born on 22 July 1862. He was the son of the Honourable Cosmo Lewis Duff-Gordon and was the Fifth Baronet of Halkin. The title derived from a licence given to his great uncle for recognition of his aid to the Crown during the Peninsular War (1807-14).

He was a great fencer and represented Great Britain at the 1906 Intercalated Games where he won a silver medal.

Sir Cosmo and his wife Lady Lucy Christina Duff-Gordon (accompanied by her secretary, Miss Francatelli) set sail on the maiden voyage of the Titanic in April 1912. The three of them survived after gaining a place on Lifeboat No. 1.

Criticism followed his rescue because of the violation of the woman and children first rule. It was also alleged that he had offered crew members a bribe not to return to rescue surviving passengers in the water once Titanic had sunk will. Sir Duff-Gordon denied the allegations.

On day 10 and 11 of the British Inquiry, Sir Duff-Gordon gave his testimony. He was examined by the Attorney-General. See Appendix 10, p. 235 for his testimony but extracted below. [The number represents the question number asked at the Inquiry] 12585. Will you tell us about that?

- I will. If I may, I will tell you what happened.

12586. Yes?

- There was a man sitting next to me, and of course in the dark I could see nothing of him. I never did see him, and I do not know yet who he is. I suppose it would be some time when they rested on their oars, 20 minutes or half-an-hour after the Titanic had sunk, a man said to me, “I suppose you have lost everything” and I said “Of course.” He says “But you can get some more,” and I said “Yes.” “Well,” he said, “we have lost all our kit and the company won't give us any more, and what is more our pay stops from tonight. All they will do is to send us back to London.” So I said to them: “You fellows need not worry about that; I will give you a fiver each to start a new kit.” That is the whole of that £5 note story.

12587. That was in the boat?

- In the boat. I said it to one of them and I do not know yet which.

12588. And when you got on the “Carpathia”?

- When I got on the “Carpathia” there was a little hitch in getting one of the men up the ladder, and I saw Hendrickson. It was Hendrickson that I saw distinctly, when he brought my coat, which I had thrown in the bottom of the boat. He brought it up after me, and I asked him to get the men's names, and that list, in my belief, is his writing. It is merely a list of the names, and I think it is in Hendrickson's writing.

12589. Did you know either of the other two male passengers?

- No, I did not know them, not till the next day.

12590. They were Americans?

- Yes.

12591. Did you say anything to the Captain of the “Carpathia” of your intention to give that money to the men?

- Yes; I went to see him one afternoon and told him I had promised the crew of my boat a £5 note each, and he said, “It is quite unnecessary.” I laughed and said, “I promised it; so I have got to give it them.”

The Telegraph reported on 13 April 2012 that evidence found from letters and notes could vindicate the Duff-Gordons. Elizabeth Grice reported:

“Just when it could safely be assumed that every rivet of the Titanic had been examined, every myth exhausted and every survivor story told, chance has thrown up a rich hoard of new material written by two of the most vilified first-class passengers to escape drowning.

The letters of Sir Cosmo Duff Gordon and his colourful wife, Lucy, are an extraordinary record of the night of April 15 1912, a century ago tomorrow. They describe not just the unfolding terror of the ship’s sinking, but every detail of how they dressed for the emergency, what they took with them, and their experiences in a perilously small boat before they were picked up by the RMS Carpathia.

There is even a complete inventory of all Lady Duff Gordon’s possessions that went to the bottom of the sea, from feather boas, teagowns and long kid gloves to silk corsets, diamonds and pearls. Head of a famous fashion house, Maison Lucile, she took three fur coats, a large fox fur and seven hats on the voyage to New York. The total value is given as £3,208 3s 6d (around £250,000 today).

The documents have been in a cardboard box in a solicitor’s room for the past 100 years and only came to light when two summer vacation students at the London office of Veale Wasbrough Vizards (the firm that merged with Tweedies, who represented the Duff Gordons) were asked to work through old papers that might be returned to the families of their original clients.

The historical significance of the find is that it contains fresh detail that could finally restore the good name of the Duff Gordons, who were accused of urging, or even bribing, the crew of their boat to row away from the sinking ship and not to pick up survivors, even though the boat wasn’t full. Though they were cleared of all blame by the Board of Trade inquiry in May 1912, they were savagely cross-examined and remained tainted by suspicion that they had acted selfishly.” He was the son of the Right Honourable Thomas Andrews and Eliza Pirrie. He was the nephew of Lord Pirrie owner of Harland and Wolff.

From 1884, he attended the Royal Belfast Academical Institution. At the age of 16, he left the institution and took up an apprenticeship at Harland and Wolff.

His apprenticeship lasted two years. He spent the first three months in the joiner’s shop, a month with the cabinetmakers, two months working on the ships and eighteen months in the drawing office.

In 1901, he was made a member of the Institution of Naval Architects and was involved in the construction of the WSL’s “Big Four.” He also designed the SS Nomadic. The Nomadic completed her most famous task by transferring the excited First and Second Class passengers from the shallow dockside in Cherbourg out to the Titanic, which was moored in deeper water just off shore. In awe of the WSL luxury and ground breaking design, those passengers were blissfully unaware of the tragic fate awaiting many of them only days later.

In 1907, he became the managing director and head of the drafting department at Harland and Wolff. It was at this time, that he was overseeing plans for the new “Olympic class” liners for the WSL. The plans were designed by Andrews, Lord William Pirrie and the general manager at Harland and Wolff, Alexander Carlisle.

Before the plans were completed, Andrews and Carlisle had suggested that the Olympic and the Titanic should carry 46 lifeboats but it was thought that too many lifeboats would not instil confidence in the voyage and would be unsightly. They also suggested that the watertight compartments should be extended up to B-Deck to prevent water spilling over into the other compartments. Their suggestions were not taken up by the WSL.

On completion of the Titanic, The Harland and Wolff Guarantee Group, led by Andrews, sailed on the Titanic. It was their job to observe how the ship operated and would make notes for any necessary improvements. Andrews was often seen walking around the ship with a notepad and paper in his hand. He boarded the Titanic with ticket number 112050.

Shortly after the collision, Captain Smith asked Andrews to inspect the damage and to make a report. Andrews went to the damaged section and obtained reports from engineers and other officers on the damage. He calculated that the first five of the ships watertight compartments were flooding. He knew that it was a “mathematical certainty” if more than four compartments were flooded the ship would inevitably sink. He calculated that the ship would sink in an hour or so. The ship sank in just over 2½ hours.

Andrews remained on board and he searched cabins, and state rooms telling passengers to put on lifebelts and go to the boats.

Shaun Bullock in his book “Thomas Andrews: Shipbuilder” published in 1912, wrote that John Stewart, a steward on the Titanic, saw Andrews in the First Class Smoking Room staring at the painting “Plymouth Harbour” just 10 minutes before the ship sank. Stewart left the ship at 1:40 a.m. Some passengers saw Andrews on the Boat Deck throwing deck chairs to passengers in the water.

His body was never found. He left behind his wife Helen Riley Barbour and his daughter Elisabeth Law Barbour Andrews.

He was seen as a hero of the hour. On 22 April 1912, the Times newspaper wrote “James Moore, of Belfast, has received the following from a survivor in New York in reference to Mr Andrews; ‘heroic unto death thinking only of safety of others’.” Another telegram read; “When last seen, officers say was throwing deck chairs, other objects, to people in water. His chief concern safety of everyone but himself.”

A Memorial Hall on Ballygowan Road, Camber was named after him and was opened by his widow on 22 February 1915. Arthur Rostron was born on 14 May 1869 in Astley Bridge, Lancashire, England. He attended the local grammar school for a year in 1882 and the Bolton Church Institute in 1884.

He joined the merchant Navy as a cadet and was commissioned as a supplement and in the Royal naval reserve on 28 April 1893. Whilst serving as second mate on the Concord, in December 1894 he passed his extra master’s certificate.

He joined the Cunard Line in January 1895 and became the fourth officer on the Umbria. Following his experiences and learning on the Umbria he was transferred to several other ships including the Saxonia and the Cherbourg.

In 1907, he was due to join the crew of the Lusitania but a few days before her maiden voyage, he was transferred to the Brescia and continued to serve on the Mediterranean route for several years.

On 18 January 1912, he was given command of the Carpathia on the New York to Fiume route. The Carpathia sailed from Pier 54 in New York to Fiume with almost 750 passengers on board; 125 First Class passengers, 65 Second Class and 553 Third Class.

When the Titanic struck the iceberg, Rostron was asleep in his cabin, off duty. His wireless operator, Harold Cottam, woke him up and told him about the Titanic’s distress call. The Carpathia was over 60 miles away from the Titanic. Immediately, he gave orders to change course and head towards the sinking liner. The ship managed to sail at 17.5 knots for 3½ hours to reach the Titanic’s location. The Carpathia arrived at the scene at 4 a.m., and an immediate rescue operation began.

712 people were rescued (a couple of passengers died later) together with the lifeboats. Captain Rostron sailed back to New York because there were insufficient provisions on board to make it to Europe. At this time, there were over 1400 passengers on board the Carpathia.

Captain Rostron was highly praised for his efforts in both the American and British Inquiries.

On 29 May 1912, he was awarded a silver cup and a gold medal by the survivors. It was presented by Margaret Brown (“The Unsinkable Molly Brown”). He was received by President Taft at the White House and given the Congressional Medal of Honour. He also received the American Cross of Honour, the Liverpool Shipwreck and Humane Society medal and the Shipwreck Society of New York medal.

Following the sinking of the Titanic and the subsequent inquiries, he continued to command more Cunard ships. In September 1915, he commanded the Mauretania when she was a hospital ship. Following a short break, and transfer to the Ivernia, he returned to the Mauretania until 1926.

He was appointed Commodore of the Cunard fleet. In 1919, he was made Commander of the order of the British Empire and Knight Commander of the order of the British Empire in 1926. He earned the freedom of New York ‘for his splendid service to humanity to the city of New York and to the people of the United States of America over many years.”

He retired in May 1931 and wrote his memoirs “Home From The Sea.” He died on 4 November 1940. Harold Sydney Bride, was born on 11 January 1890 in Nunhead, South London.

After leaving primary school, he wanted to be a wireless operator. To help him finance his training, he worked for the family business. He completed his training for the Marconi Company in July 1911 and continued in their employment.

In 1912, he joined the crew of the Titanic as the junior wireless operator under Jack Phillips. His monthly wage was £2. 2s 6d.

During the voyage, the ship’s wireless operators sent and received messages for the passengers. The Wireless Room was on the Boat Deck. They received several iceberg warnings.

On the evening of the Titanic disaster, Bride, was not on duty. He retired early so that he could relieve Phillips at midnight. The day had been particularly busy because the wireless had not been working and there was a backlog of messages to be sent to Cape Race in Newfoundland.

Bride, woke shortly after 11.40 p.m., as a result of the ship colliding with the iceberg. Captain Smith instructed the operators to send out distress signals. Phillips sent out the CQD signal and Bride took response messages to the captain. Bride, suggested to Phillips that the new SOS should be tried because “it may be his last chance to send it.”

As water crept up the Boat Deck, Bride, was washed off the deck and found himself under the overturned Collapsible B which had been washed overboard as well. He climbed on the top of the boat from where he was transferred into another lifeboat until finally rescued by the Carpathia.

His account of the disaster was exclusively given to the New York Times who reported it on 19 April 1912. The story was entitled “Thrilling story by Titanic’s surviving Wireless Man.” Click here for the complete account. Bride, testified at both Inquiries about the warnings received that night. Bride, continued with his career as wireless operator until his retirement.

He died on 29 April 1956 in Glasgow. Henry Tingle Wilde (pictured left) was born on 21 September 1872 in Walton, Liverpool. His parents were Henry Wilde, an insurance surveyor from Ecclesfield and Elizabeth Tingle. He was christened at the Loxley Congregational Chapel on 24 October 1872.

In 1889, he began his four-year apprenticeship with James Chambers & Co. in Liverpool. After completion Wilde remained with the company and served as Third Mate on both the Greystoke Castle and the Hornsby Castle.

He joined the Maranhan Steamship Company after gaining his Second Mate’s Certificate and served as Third Officer on board the SS Brunswick but was later promoted to Second Officer. After gaining his Masters Certificate in 1896, he commenced employment with the Elder Dempster lines on board SS Europa serving as Second Officer.

In July 1897, he joined the WSL and gained experience whilst serving on many ships: Covic, Cufic, Tauric, Delphic, Arabic, Cedric, Celtic2, Cymric, Laurentic1, Medic, Megantic and the Teutonic.

On 3 August 1898, Wilde married Mary Catherine Jones in the Welsh Calvinistic Methodist Chapel in Liverpool and had four children between 1900 and 1908.

During this time with the WSL, he obtained his extra master’s certificate in the Merchant Navy and was made a Lieutenant in the Royal Naval Reserve in 1904.

On 19 November 1910, Mary gave birth to twin boys, Archie and Richard, who both sadly died shortly after birth: Archie aged 14 days and Richard 25 days. Mary herself passed away on Christmas Eve in 1910. Wilde became a widower with four young children.

In August 1911, Wilde became Chief Officer on the RMS Olympic, serving under Captain Edward J. Smith with William Murdoch acting as Second Officer. Chief Purser Hugh McElroy also gave service. All three officers would serve on the Titanic in April 1912.

During the maiden voyage of the Titanic, Wilde wrote to his sister and told her that he had “a queer feeling about the ship."

When the Titanic collided with the iceberg, Wilde would have been in his cabin on the boat deck. He inspected the forepeak and went to the Bridge to report to Captain Smith.

On two occasions during the evacuation Second Officer Lightoller thought Wilde was taking too long in launching the boats and consulted with Captain Smith. Wilde filled and lowering the even-numbered lifeboats on the port side and when some of the passengers panicked leading to pushing and shoving, he gave firearms to both Lightoller and Murdoch to help calm the situation.

When most of the boats had been lowered by 1.40 a.m., Wilde moved to the starboard side to help lower the remaining boats

Wilde did not survive the disaster and his body was never recovered. There have been various accounts of his final moments onboard which have included testimony that he was seen smoking a cigarette on the Bridge, washed into the sea whilst trying to free Collapsible Boat A and he died of hypothermia whilst swimming to Collapsible Boat B. Some witnesses (Third Class passenger Edward Dorking) claimed he made it to Collapsible B but died whilst holding on to the boat and his body sank before being picked up. James Paul Moody was born in Scarborough, England on 21 August 1887. His parents were John Henry Moody and Evelyn Louis Lammin. Moody attended the Rosebery House School before joining HMS Conway as a cadet in 1902. For two years he gained experience which counted for one years' sea time towards his Board of Trade Second Mate's Certification.

In 1904, he joined the William Thomas line and served on board the Boadicea as an apprentice. During a voyage across to New York there was a terrible storm, so bad that one of his fellow apprentices committed suicide. Moody continued to gain experience and gained his Second Mate's Certification and later his First Mate’s Certificate after gaining experience in steam, early oil-tankers and cargo vessels.

In 1910, he studied at the King Edward VII Nautical School in 1910, which prepared him for the Board of Trade examinations, the Ordinary Master's Certification which he successfully obtained. Also that year, he became Sub-Lieutenant when he received a commission in the Royal Naval Reserve (RNR). It was a requirement of the WSL that their officers should serve in the RNR so that the company would receive benefits from the British Government as well as illustrating their officers were competent mariners.

In 1911, he joined the Oceanic2 as Sixth Officer and in March 1912 was transferred to the Titanic to also serve as the Sixth Officer.

When the iceberg was seen by Frederick Fleet at 11.40 p.m. on 14 April 1912, Moody was on duty on the Bridge with First Officer William Murdoch and Fourth Officer Joseph Boxhall. Moody answered the call from Frederick Fleet warning him about the "Iceberg, right ahead!"

During the evacuation, Moody assisted on the port side with the loading of Lifeboats Numbers. Whilst loading No. 14, Moody turned down Lowe’s order to man the boat and decided to remain on the ship. Lowe manned the boat instead. Moody then went to the starboard side to help Murdoch.

He was last seen by Samuel Hemming, the ship's lamp trimmer on top of the officers' quarters trying to launch the emergency Lifeboat Collapsible A. He was the only junior officer who did not survive.

A monument in Woodland Cemetery, Scarborough, commemorates Moody's sacrifice on the Titanic with the inscription, "Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends."

On the 19 April 1912, the WSL wrote a letter to his family pointing out that he gave up his seat in the lifeboat and was a hero. The letter was recently found and sold on Ebay.

On 14 April 2015, the Daily Mail reported that an “amazing letter reveals for the first time how Titanic owners demanded huge sums from grieving families to be reunited with bodies of ship's crew.” The letter, dated 7 May 1912, was sent from WSL to James Moody’s brother, Christopher Moody, and demanded a deposit of £20 (£2,200 today) for “expenses and any land charges” in America and any “arrangements and expenses for taking charge of the remains” would be added to Christopher Moody’s account. The body of James Moody was never recovered and at the time of writing the WSL would have known this. The letter certainly paints the WSL in a bad light and such a contrast from the warm letter dated 19 April 1912. William Murdoch was born on 28 February 1873 in Dalbeattie in Kirkcudbrightshire (now Dumfries and Galloway), Scotland. His parents were Captain Samuel Murdoch, a master mariner, and Jane Muirhead. He was a pupil at the old Primary School and then studied at Dalbeattie High School in Alpine Street where he was awarded his diploma in 1887.

He was apprenticed for five years to William Joyce & Coy, Liverpool and gained his Second Mate's Certificate on his first attempt after just four years. As an apprentice he served on board the Charles Cosworth of Liverpool and from May 1895, he was First Mate on the St. Cuthbert, which sank in a hurricane off Uruguay in 1897.

In 1896, at the age of 23, Murdoch gained his Extra Master's Certificate at Liverpool. After which, in 1897, he was First Officer on the Lydgate, a 2,524-tonne barque operated by J. Joyce & Co.

Over the next 12 years his maritime experience grew and he progressed up the ranks from Second Officer to First Officer. He served on a successive number of White Star Line ships including the Medic (1900, serving with Charles Lightoller), the Runic in 1901, the Arabic in 1903, the Celtic in 1904, the Germanic (1904), the Oceanic (1905), the Cedric (1906), the Adriatic (1907–1911), the Olympic (1911) and finally the Titanic (1912).

It is notable that whilst serving on the Arabic in 1903, Murdoch disobeyed a direct order from Chief Officer Fox to steer hard-a-port to avoid collision with another ship. Instead, he held the ship’s course and narrowly avoided collision which would have happened had the order been obeyed. It is said that the Master of the ship, Captain Bertram Hayes, was pleased with the intuition Murdoch showed. Captain Hayes went on to be Master of the HMHS Britannic (the Titanic’s sister ship)

Murdoch served as First Officer on the Olympic which required experienced crew members. Captain Edward J. Smith assembled a fine crew which included Henry Wilde as Chief Officer and Chief Purser Hugh McElroy. All three officers would serve on the Titanic the following year.

On 20 September 1911, the Olympic started her fifth voyage to New York and collided with the HMS Hawke causing considerable damage to both ships. At the time of the collision, Murdoch was at his docking station at the stern of the ship. He was called to provide testimony at the Inquiry that followed.

Originally, Murdoch was going to be appointed Chief Officer on board the Titanic for her maiden voyage in April 1912, however, Captain Smith appointed Henry Wilde as Chief Officer which meant Murdoch became the First Officer and Charles Lightoller became the Second Officer.

Murdoch has become a figure of controversy, with mystery surrounding the circumstances of his death and his actions during the collision with the iceberg.

At the time of the collision with the iceberg, Murdoch was on duty on the Bridge. At approximately 11:39 pm on 14 April 1912, an iceberg was sighted by Frederick Fleet, a Titanic lookout up in the crow’s nest. After Fleet reported the iceberg sighting to the Bridge, Murdoch gave the order to "Hard-a-starboard". This was confirmed by Quartermaster Robert Hichens, who was at the helm, and by Fourth Officer Joseph Boxhall.

Fourth Officer Boxhall testified at the British Board of Trade Inquiry that Murdoch set the ship's telegraph to "Full Astern", but Greaser Frederick Scott and Leading Stoker Frederick Barrett testified that the stoking indicators went from "Full" to "Stop". At some point either during or just before the collision he may also have given the order of “hard-a’port” as testified by Quartermaster Alfred Olliver as he walked onto the bridge during the collision. Different testimonies have led to questions about the actual orders Murdoch gave.

After the collision, Murdoch was charged with the starboard evacuation and launched ten lifeboats. He was last seen launching Collapsible Lifeboat A and was not one of the survivors picked up. His body was never recovered. Eugene Daly (a Third Class passenger) and George Rheims (a First Class passenger) testified that they saw an Officer committing suicide by gun shot at the forward lifeboat station near where Murdoch was last seen. It is possible that in order to save Murdoch’s widow from the ordeal he testified that he saw Murdoch being swept into the sea by a wave. This is probably not true because the testimony which was given at the US Senate Inquiry contradicts Lightoller’s whereabouts and that he may not have seen Murdoch. Before the British Board of Trade Inquiry commenced, the Town Council of Dalbeattie decided to erect a monument in honour of William Murdoch.

In 1997, James Cameron released the blockbuster movie, “Titanic,” and Murdoch’s character was portrayed with incompetence and depicted Murdoch’s alleged suicide. Murdoch’s nephew criticised the portrayal and Cameron reacted by donating money to establish a charitable prize in Murdoch's name.

Some of Murdoch’s belongings (toiletry kit, a spare White Star Line officer's button, a straight razor, a shoe brush, a smoking pipe, and a pair of long johns) were recovered during a dive to the Titanic in July 2000 by David Concannon, Ralph White and Anatoly Sagalevitch. He received part of his nautical training in the Navigation Department of the Merchant Venturers' Technical College and qualified as Second Mate in June 1902 and Master Mariner in August 1906. His four year apprenticeship with James Nourse Ltd was followed by a five year training course as a Deck Officer.

In 1906 he joined the White Star Line and served as Fourth, Third Officer on the Dolphin and Second Officer on the Majestic and as Fourth Officer on the Oceanic.

In April 1912 he was appointed Third Officer on the Titanic. His duties included working out celestial observation and compass deviation, general supervision of the decks, looking to the quartermasters, and relieving the Bridge officers when necessary.

At the time of the Titanic collision with the iceberg, he was not in duty but was dressing for his watch. Fourth Officer Boxhall went to his cabin and informed him they had struck an iceberg and were taking on water. Pitman had no idea of the extent of damage caused by the iceberg.

At about 12.20 p.m. Pitman was ordered to report to the starboard side of the ship to assist in uncovering lifeboats. After receiving the command to lower the boats, Murdoch ordered Pitman to take charge of Lifeboat No. 5. Bruce Ismay told Pitman to “get it filled with women and children.” Pitman replied that he would await the orders of Captain Smith. Pitman went to the Bridge and explained to the captain what had been said, to which he replied, “Carry on.” He obeyed and returned to the lifeboat. Before Pitman entered the lifeboat, Murdoch shook his hand saying "Goodbye; good luck." Pitman, testified at the British Board of Trade inquiry that there were about 30-40 women, two children and five officers (including himself) in the lifeboat. He was ordered to pick up more passengers from the gangway but the door did not open. He waited about 100 yards off from the ship and he could see the head of the ship disappearing in to the water.

“I watched the different lines of light disappear.”

Pitman wanted to turn back and rescue survivors in the water. His idea was met with protest and he decided to remain as is. Such lack of action haunted his consciousness for the rest of his life.

At the British Inquiry, he was asked by Mr Butler Aspinall whether he thought that the Titanic broke in two and before finally foundering, the after part righted itself and then plunged into the sea. Did she crack in the middle? Pitman did not think so.

Lifeboat No. 5 was picked up the RMS Carpathia and arrived at Pier 54 in New York City with the rest of the survivors on 18 April 1912.

After the disaster, Pitman continued to serve with the White Star Line on the Oceanic and Olympic. He left the White Star Line in the early 1920s, served in the Second World War and retired from over 50 years at sea in 1946. He died on 7 December 1961 and was buried at Pitcombe Parish Church, Somerset. Boxhall maintained a diary (now at the Hull Maritime Museum) in which he writes about his experiences as an apprentice aboard the sailing ship, Cumbrian Warrior, a barque of the William Thomas Line of Liverpool. His four-year apprenticeship began on 2 June 1899.

In 1903, he joined the Wilson Line where his father was already employed as Master. He studied for his Master's and Extra-Master's certifications which he obtained in September 1907 and joined the White Star Line. He served on White Star's liners Oceanic and Arabic. He was confirmed as sub-lieutenant in the Royal Naval Reserve (RNR) on 1 October 1911. At the age of 28, he transferred to the Titanic as Fourth Officer.

Boxhall was one of the last officers to leave the Titanic and took charge of one of the lifeboats. Later he gave evidence at the inquiry in the United States and the Board of Trade Inquiry in England.

At the Inquiries, Boxhall recalled that he was almost on the bridge when Titanic struck the iceberg and he heard the First Officer give the order “Hard-a-starboard.” Captain Smith arrived on the bridge and asked Murdoch for an account of what had happened.

During an interview on BBC Radio in 1967 he gave his account of events:

“I was about halfway between the officers’ quarters and the bridge when the crash came. It didn’t break my step.” He headed to the Bridge where Captain Smith ordered him to inspect the forward part of the ship. He went to F Deck to make his inspection but found no damage and returned up a staircase to C Deck where he came across a man who was holding a piece of ice about the size of a small basin. He did find a little ice in the well deck. He returned to the bride to report to the captain who ordered him to find the carpenter. The carpenter told Boxhall that the ship was making water fast. He went down to the mail room.

“I saw bags of mail floating by,” he said. “I realised then it was serious.” Water was within feet of G Deck.

Boxhall returned to the Bridge and calculated the Titanic’s position as being 41°46N 50°14W so that the wireless room could transmit their position and radio for help using the Marconi Wireless. He was ordered to fire the ship’s distress flares.

Whilst on deck, Boxhall through his binoculars, sighted the lights of a ship he thought was the SS Californian heading towards them.

“This steamer approached and approached until you could see all her lights with the naked eye. And I should say she must have been within five miles,” he said. “Then, eventually, she turned away and showed a stern light.”

Boxhall was placed in charge of Lifeboat No. 2, which was lowered from the port side at 1.45 a.m. The British Board of Trade Inquiry recorded only 26 persons were rescued from it (it could carry 40). To avoid the lifeboat from being pulled under by suction caused by the Titanic’s enormous propellers, he rowed away from the doomed ship. Boxhall said that he saw the lights go out but the Titanic was too far away to see if she had sunk or not. He heard the screams of passengers and crew even though he was about three-quarters of a mile away.

“We realised she'd gone and we heard all the screams... we couldn't do anything,” he said.

At 4 a.m. the RMS Carpathia was spotted and rescued the survivors, returning to Pier 54 in New York on 18 April 1912.

After giving testimony at the American Inquiry, Boxhall and his colleague officers returned to England on the Adriatic2 on 2 May 1912. On their return, they would provide further testimony at the British Board of Trade Inquiry.

Boxhall continued service with the White Star Line after the loss of the Titanic and became Fourth officer on the Adriatic for a short time.

During the First World War he was commissioned to serve on the battleship HMS Commonwealth and was a commander of a torpedo boat. He was promoted to Lieutenant on 27 May 1915.

After the War, his service for the White Star Line resumed. He married in March 1919.

On 27 May 1923, he was promoted to Lieutenant-Commander in the RNR and on 30 June 1926 became the Second Officer on the Olympic. After the merger of the WSL and the Cunard Line in 1933, he served on the RMS Aquitania. He retired in 1940.

In 1958, he was a technical advisor for the film production “A Night To Remember”, based on Walter Lord’s novel.

In 1967, he died after being hospitalised and his ashes were scattered on the position he had calculated as bring the Titanic’s foundering position.

Captain Stanley Phillip Lord (1877-1962)

JP Morgan (1837-1913)

Harold Godfrey Lowe (1882-1944)

Sir Cosmo Edmund Duff-Gordon (1862-1931)

Thomas Andrews (1873-1912)

Sir Arthur Henry Rostron KBE RD RNR (1869-1940)

Harold Sydney Bride (1890-1956)

Henry Tingle Wilde (1872-1912)

Wilde’s role in the Titanic disaster

James Paul Moody (1887-1912)

Moody’s role in the Titanic disaster

William McMaster Murdoch, RNR (1873-1912)

Murdoch’s role in the Titanic disaster

Herbert John "Bert" Pitman MBE (1877-1961)

Joseph Groves Boxhall RNR (1884-1967)

Boxhall’s role in the Titanic disaster