The Maiden Voyage, Disaster and Sinking of RMS Titanic

A bad start: a near collision and a fire!

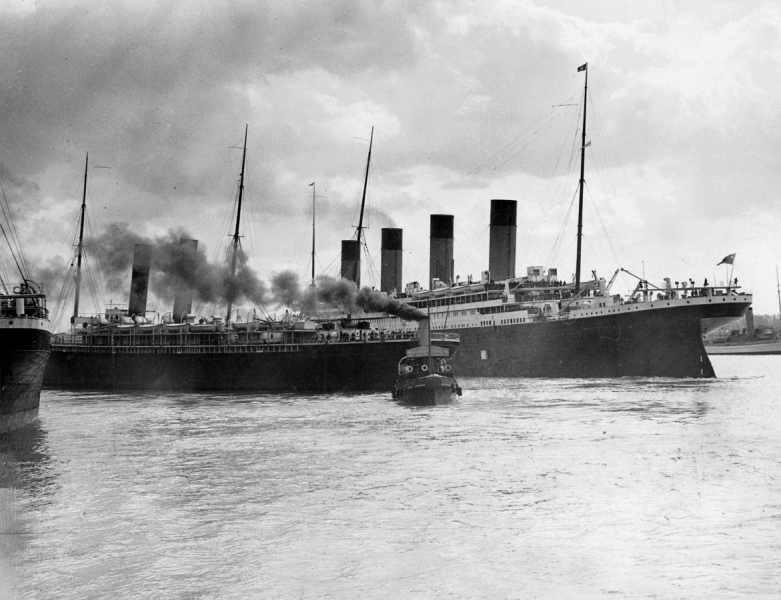

On 10 April 1912, the Titanic was finally ready, after delays, for her departure on her maiden voyage. These occurred when the Olympic collided with the HMS Hawke in September 1911 and again when the Olympic lost a propeller in February 1912. The owners wanted to make sure that the Olympic was operational to generate revenue for the WSL.

Also at the time, there was a coal strike: a severe problem for any transatlantic liner. Ships like the Titanic, would consume over 600 tons of coal a day. To solve the problem, coal was taken from other ships including the Adriatic and the Oceanic, to stock up the coal bunkers for the Titanic's voyage.

RMS Titanic nearly collided with the SS New York

This is exactly what happened to the Olympic when she collided with the HMS Hawke in September 1911 (see Olympic section).

Captain Smith knew what he had to do and ordered the engines “full stern ahead” which brought the helm over. It was a near miss, but a collision was averted. The Titanic sailed to Cherbourg, France and docked with the help of two tenders, the Traffic and the Nomadic. There, the Titanic took on board more passengers, luggage, cargo and mail. 24 passengers disembarked. At 8.10 p.m., she was underway again.

She arrived at Queenstown in Ireland on 11 April 1912 at 11.30 a.m. where she picked up additional passengers and 1385 sacks of mail.

At 1.30 p.m., the Titanic left Queenstown bound for New York. She would take the standard route across the Atlantic cruising at around 20 knots. There were 1316 passengers and 885 crew according to Board of Trade Inquiry official figures.

For a passenger list please download our PDF version.

A fire had started in coal bunker No.6 before the Titanic sailed. The captain knew about it and told his crew to play down any speculation. Passengers were therefore unaware that a fire in one of the coalbunkers had been burning. It was not extinguished until Saturday 14 April 1912. A team of 12 men attempted to put out the flames, but it was too large to control, reaching temperatures of up to 1000 degrees Celsius.

Coalbunker fires were common because coal dust, which is very flammable, got everywhere, not just in the air but in machinery. The slightest spark could ignite the whole bunker so coal had to be continuously kept sufficiently damp to prevent fires.

On 12 April 2008 and on 1 January 2017, the Independent newspaper wrote articles about the fire on board. In the January article, they reported that newly discovered photographs taken over the construction period of the Titanic led experts to be able to prove that the fire burned for several weeks before the Titanic sailed. They believe that intense heat from the fire warped and weakened the double hull at the place where the iceberg struck. As water poured into the neighbouring compartment, pressure built up which caused the damaged bulkhead to give way quicker than it would undamaged.

The coal supply on board was finite and some would have been lost in the fire. It could be argued that the captain and the WSL management (Ismay) could have calculated that the ship would run out of coal before reaching New York. This would have been disastrous for the prestige of the WSL. By maintaining a constant speed, the remaining coal would have been burned efficiently and would have given a better chance of arrival at their destination. Does this partially explain why the Titanic travelled at excessive speed? If the ship travelled at varying speeds, the coal would have depleted too soon.

Apart from the fire, the first few days of the voyage were uneventful. Captain Smith steadily increased speed each day. Reports showed the ship covered 386 miles on the first day, 519 the second and 546 miles the third. Passengers enjoyed the space on the Promenade Deck and being able to relax. The crew had settled into their strict routine. The captain carried out his daily inspection of all areas even the kitchens. Afterwards, he would mingle with the First Class passengers and give them reassurance that they were being well catered for.

On Sunday 14 April 1912, Captain Smith did not carry out his usual inspection but worked in his cabin and received the reports from his officers. He held a religious service in the First Class Saloon at 10:30 a.m. Colonel Archibald Gracie (a First Class passenger) was impressed with the “Prayer For Those At Sea.” Gracie described his experience in his book called “Titanic”. Usually, after this service a boat drill was carried out, but on this occasion Captain Smith did not do so. The Board of Trade Inquiry noted this omission in their final report

The Baltic sent the Titanic an ice warning at 1.42 p.m., which read “Greek steamer Athenai reports passing icebergs and large quantities of field ice today in 41° 51' N, 49° 52' W. Wish you and Titanic all success. Commander.” Captain Smith and Ismay were on the Bridge at the time and both read the message. As a precaution, Smith altered course southward, even though the Athenai was further north.

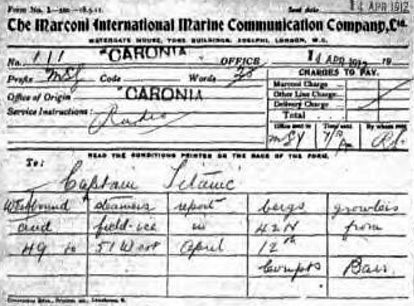

Throughout much of the day, the Titanic received further ice warnings.

For a complete list of ice warnings and messages sent and received by the Titanic click here.

The Titanic’s Junior Wireless Operator, Harold Sydney Bride (pictured)intercepted a message from the Amerika warning of ice. The next arrived three minutes after the one from the Baltic. It read, “Amerika passed two icebergs in 41° 27' N, 50° 8' W.” The Caronia warned of field ice, a term used to describe a floating mass of ice low lying across the water. Icebergs are huge masses of ice with only 10% of which is visible above the waterline.

Ice itself did not pose a threat to shipping lines. The appropriate action to remain safe would be to either slow down or change course. Captain Smith took the latter.

At 10:15 p.m., the Carpathia which was sailing about four hours ahead of the Titanic, actually stopped because of a large amount of ice. Three hours earlier, the Californian had sighted a large iceberg ahead. Her captain, Stanley Phillip Lord, gave the order to steer around it. He also gave the Californian’s Wireless Operator, Cyril Furmstone Evans orders to send out ice warnings to all ships. The message was received by Harold Bride at 7.30 p.m. He took it to the Bridge where Second Officer Charles Lightoller and Fourth Officer Joseph Boxhall noted the warning and reported it to Captain Smith when he returned to the Bridge after dinner.

Captain Smith retired to his cabin at 9.20 p.m. after receiving this report from Lightoller. Lightoller’s watch ended at 10 p.m. and First Officer William Murdoch took over. Boxhall was replaced by Sixth Officer James Paul Moody.

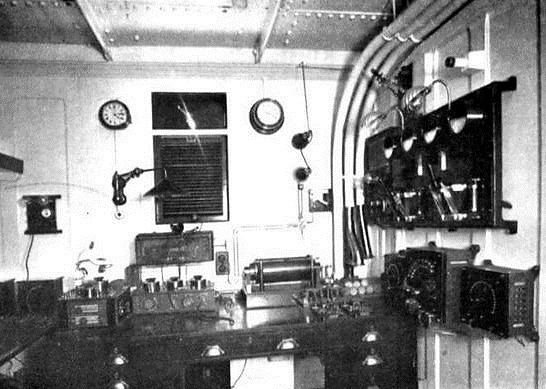

In the Wireless Room, Senior Wireless Operator, John George Phillips and Harold Bride, were busy catching up with passenger messages. The wireless had been out of service for most of the day and there was a huge backlog to get through. Wireless Operator Cyril Evans, from the Californian, sent the Titanic an ice warning. Phillips replied, “Shut up. I am working Cape Race!” Evans listened for a while before turning his radio off.

"Iceberg Dead A-Head"

The Titanic cut the waves like a knife through butter at a steady speed of 22.5 knots. It was 11.40 p.m. on 14 April 1912 and visibility was clear.

Suddenly, Frederick Fleet (24) (pictured) observed an iceberg heading straight for the ship. He grabbed the chord of the alarm bell (which is on the Bridge) and pulled it three times, sounding the alarm on the Bridge. Sixth Officer James Moody asked him in a calm voice:

“What do you see?”

“Iceberg right ahead!”

“Thank you,” replied Moody who repeated the message to First Officer William Murdoch. Murdoch gave the orders “to stop and go full speed astern and put the helm over hard to starboard”.

He quickly closed all watertight doors. After he had sounded the alarm, Fleet and his colleague, Reginald Lee, waited for ship to react. The bow was moving very slowly to port.

Minutes seemed to pass but in reality it was only thirty-seven seconds before the ship began to swing portside. The Titanic hit the iceberg with her starboard side and suffered a major longitudinal gash.

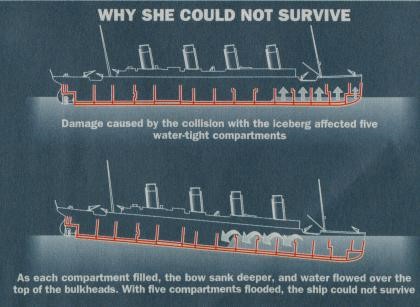

Damage to RMS Titanic caused by the iceberg

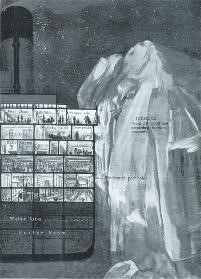

The watertight doors were closed quickly but due to the extent of the damage they would only slow down the rate of sinking. Captain Smith accompanied Thomas Andrews to carry out structural surveys. Andrews knew every inch of the ship and had been carrying out inspections since the beginning of the voyage.

As a result of seeing water in the forepeak, No. 1 and No. 2 hold, boiler rooms No. 5 and 6 and the mailroom, Andrews calculated that there was a 300 foot gash with five compartments already flooded.

Her design allowed the Titanic to float with any three of her five compartments flooded at any one time: but five meant certain sinking. Sinking was “a mathematical certainty,” said Andrews to the captain. How long the ship would stay afloat was in question. Andrews estimated that the ship would last an hour or an hour and a half.

With the fate of the Titanic sealed, Captain Smith gave several orders to his officers. Chief Officer Wilde was in charge of removing the covers from the lifeboats. Murdoch was charged with the arousal of the stewards so that they could wake up passengers. Fourth Officer Boxall was asked to find Lightoller and

Third Officer Pitman and Moody was send to get the evacuation plans.

Evacuating a ship the size of the Titanic had not been done before. The crew were new and unfamiliar with the layout of the ship which had been designed to keep the different classes apart. During the evacuation, the Third Class passengers could not use the First Class exit routes. Despite this, the crew worked well in the disaster. Most were all experienced seamen who knew their jobs very well.

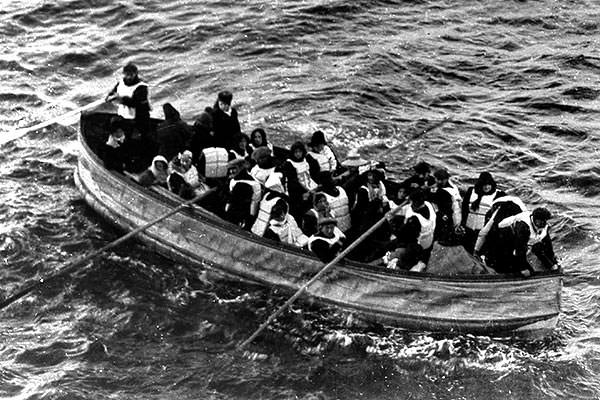

The Titanic was believed to be “unsinkable” and so the passengers on board initially did nothing. Many passengers had retired for the night and were in their cabins whilst those still awake carried on with their activities. The Third Class were particularly kept uninformed. Many of the passengers and crew would not have known or even thought about the lifeboat capacities. However, when the reality of the situation was realised, confusion and panic began. If filled, the lifeboats could only carry 1,178 people and there were 2,201 people on board.

By 12.10 a.m., water had flooded into F-Deck.

Sending SOS messages

Captain Smith went to the Wireless Room on the Boat Deck and told Phillips (pictured) what had happened.

“We've struck an iceberg……You'd better send out a call for assistance, but don't sent it until I tell you,” said the captain.

A few moments later Captain Smith gave the order. At 12.15 p.m., the International call of distress, CQD, was tapped out followed by the Titanic's MGY code. Boxhall had calculated the position of the Titanic and went to the Wireless Room to give it to the operators.According to their calculations, the nearest ship to them was the Californian only ten miles away. She heard the wireless signal but the wireless operator receiving the signal was not fully conversant with their system and so did not pick up the full message and appreciate its full meaning.

Lightoller was in charge of the portside with Wilde acting as an overseer and Murdoch, Pitman and Lowe were in charge of the starboard side evacuation. After they had finished clearing the boats away Captain Smith made his inspection and returned to the Bridge.

The Evacuation: Women and Children First

Lightoller only allowed women and children in his boats on the portside unlike Murdoch, who would allow anybody into the boats providing there was room.

Women and children should have been first off and given priority to ensure their safety. This practice was established after the wreck of the HMS Birkenhead in 1852. There were only 7 women and 13 children on board but the captain ordered his men to parade on deck whilst the women and children were lowered on the lifeboats first.

The cabin stewards in times of emergency had different tasks depending on the Class of passenger. The First Class stewards would wake up passengers and tell them to get dressed and get into lifebelts and then go and wait for their steward in the public areas. To assist the evacuation, Thomas Andrews searched cabins, and state rooms telling passengers to put on lifebelts and go to the boats.

At 12.20 a.m., Lightoller asked Wilde if the lifeboats should be swung out and was told to wait. Lightoller went to the Bridge and asked the captain for his permission which he received. Lightoller returned to his station and began to swing out the boats. Forty minutes had passed since the collision with the iceberg.

Once done, he asked Wilde if the boats should be filled, but again he was told to wait. Lightoller returned to the Bridge to clarify his orders with the captain. “Yes, put the women and children in and lower away,” said Captain Smith.

The captain suggested that Boat No. 4 was lowered down to A-Deck enabling women and children to climb on the boat easily from the Promenade Deck. It seemed that the captain had forgotten that the forward half of the Promenade Deck was enclosed. Lightoller ordered that the windows on the Promenade Deck were opened so that passengers could exit via them to the boats.

Unfortunately, they were difficult to open and Lightoller abandoned his plan and moved along to Boat No. 5. Whilst the First and Second Class passengers were required to assemble on the Boat Deck, the Third Class were confined to their sector of the ship until allowed access to the Boat Deck at 12.30 a.m.

Lightoller gave orders to some crew members to fetch the Third Class and bring them to the boats. The gangway doors were not opened and the crew whom Lightoller send down, did not reappear and were not seen again. Lightoller found himself short-handed.

A Third Class Steward, John Hart, was in charge of 58 passengers who were getting restless and so once he was given the order from Chief Third Class Steward James Kieren, he organised parties of passengers and personally escorted them to the Boat Deck. Once there, he returned to collect some more. On one trip they came across some hostile passengers who wanted to barge past the women and children and he was concerned for their safety.

In the Wireless Room, Phillips was still trying to make contact with ships. The Frankfurt responded and Phillips gave their position as being 41° 46' N, 50° 14' W.

To his great pleasure, Phillips received a response to his distress signal from the Carpathia saying she was about 60 miles from the Titanic. The message was given to Bride, who took it to the captain who was standing on the starboard side of the Boat Deck. Bride returned to the Wireless Room.

Captain Smith then ordered Quartermaster George Thomas Rowe to fetch the distress rockets and give them to Boxhall. Rowe helped Boxhall to launch the rockets at five or six minute intervals.

The last rocket was fired at 1.40 a.m. On such a clear night, the rockets should have been visible from up to twenty miles. When a rocket exploded in the air, the sound should have been heard from 5 miles away. The Californian was stationary twenty miles away. The crew on board saw the rockets and they informed their commander, Captain Stanley Lord, who told his crew that they were probably “Company rockets,” fired as a means to identify themselves to other boats. They did nothing to help at all or asked questions over the Wireless.

Boxhall and Rowe asked Captain Smith how serious the situation was. “Mr. Andrews tells me that he gives her from an hour to an hour and a half,” said the captain.

The Californian was stationary twenty miles away. The crew on board saw the rockets and they informed Captain Lord who told his crew that they were probably “Company rockets,” fired as a means to identify themselves to other boats. They did nothing to help at all or asked questions over the Wireless. Meanwhile, the evacuation continued.

Most of the Third Class passengers were unfamiliar with the layout of the giant liner. Her passages, corridors and decks must have been seen to be like a maze. Some inevitably got lost and spent their last few hours walking aimlessly around the ship trying to find their way out.

At 12.30 a.m., Boxhall saw a ship about 4 to 5 miles away. Once rescued, he recalled that he saw a ship’s masthead lights and used the Morse lamp to signal the ship but received no reply.

Under Murdoch’s supervision, Boat No. 7 was the first boat to be lowered with only 28 persons, almost half full, at 12.40 a.m. Many of the boats were launched half filled. By then, the water had already reached E-Deck.

Pitman was put in charge of Boat No. 5 by Murdoch. Bruce Ismay approached the boat and was reprimanded by Fifth Officer Lowe because he was interfering with the launch. Boat No. 5 was launched at 12.43 a.m. followed by Boat No. 3 at 1.00 a.m.

Lightoller was still shorthanded. He asked if there were any seamen in the crowd. A man volunteered himself being a yachtsman. Lightoller said that he could go on the boat if he could climb down. The man succeeded and he was the only man Lightoller allowed on the lifeboats. Passengers rallied to the lifeboats and one by one they were lowered.

With the assistance of Captain Smith and Chief Officer Wilde, Lightoller supervised the launch of Boat No. 8 at about 1.00 a.m. Male passengers helped their wives and children to their places on the lifeboats knowing that they would go down with the ship.

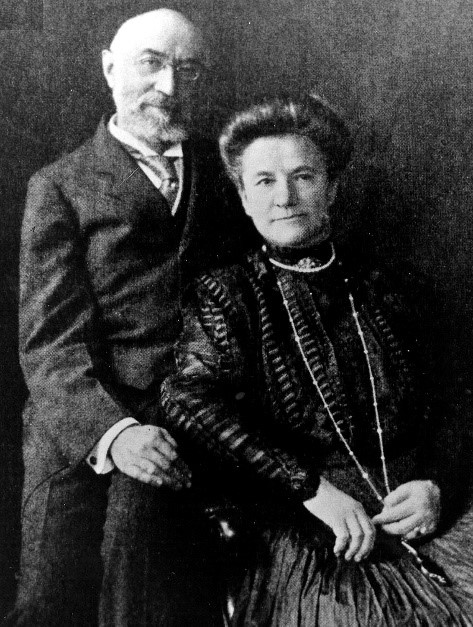

Isidor and Ida Straus refused to board Boat No. 8 while there were younger people still waiting to board. “I will not be separated from my husband Isidor Straus. As we have lived, so will we die – together.” Isidor, likewise, refused an offer to board and said “I do not wish any distinction in my favour which is not granted to others.”

Both went down with the ship - together. Some accounts state that they were last seen on the Boat Deck sitting in deck chairs holding hands when a huge wave washed them into the sea and some accounts place them in their cabin lying on the bed holding hands. Isidor Straus's body was recovered by the Mackay-Bennett and brought to Halifax, Nova Scotia, where he was identified. Ida’s body was never found.

At 1.00 a.m., Phillips replied to a message from the Olympic saying “We are sinking head down. Come as soon as possible. Get your boats ready. What is your position?”

Boat No. 1 was launched at 1.05 a.m. under the supervision of Murdoch. He allowed Sir Cosmo Duff-Gordon and his wife Lucy, Lady Duff-Gordon on board. Murdoch had allowed other married couples on board throughout the night. The lifeboat was launched with only 12 people: 7 crew and 5 First Class passengers. The boat did not return to pick up any survivors even though there was capacity for another 28 passengers. It was alleged that Sir Cosmo Duff-Gordon offered crew members a bribe of £5 to remain at a safe distance.

Boat No. 6 was launched by Lightoller with only 28 passengers at 1.10 a.m. The “Unsinkable” Molly Brown was one of the passengers.

At 1.20 a.m. Bride, took over from Phillips who went outside to see what was going on. Bride, received a message from the Baltic. She was on her way to the Titanic but was over 240 miles away! The Titanic begun to list badly and water was encroaching up stairways. No. 5 Boiler Room started to flood once the bulkhead gave way so that water now poured into six compartments.

The Frankfurt sent another message to the Titanic It annoyed Phillips because it read “Are there any ships with you already? What is wrong with you?”

Boat No. 16 was launched at 1.20 a.m. and Boat No. 14 was launched at 1.30 a.m. During the lowering of Boat No. 14, Fourth Officer Lowe thought that some panic struck passengers would jump into the boat and he fired his revolver three times in the air to warn them off.

Boat No. 12 and No. 9 were launched at 1.30 a.m. Boat No. 12 had 30 people on board and Boat No. 9 had 56 people in it.

Boat No. 11 was lowered at 1.35 a.m. with approximately 70 people on board. First Class passenger, Edith Louise Rosenbaum, carried a musical pig which was given to her as a good luck token by her mother and used it to entertain the children in the boat whilst awaiting rescue.

Boat No. 13 and 15 were launched together at 1.40 a.m., under the supervision of Murdoch, both with 65 people on board.

At 1.45 a.m. Phillips begged the Carpathia to “Come as quickly as possible, old man, engine room filling up to the boilers.” Water had indeed started to engulf the forward well deck around the cranes, the hatches and the foot of the forward mast. Captain Smith and Wilde oversaw the launch of boat No. 2, but it was only occupied by 17 people even though it could carry 40. When launched, Boxhall was placed in charge of the boat. He suggested to the passengers that they return and pick up survivors but they refused.

Once the bow had dipped under the water, the sea poured over the tops of the watertight bulkheads. The bow went further into the water raising the stern. Boat No. 10 was lowered at 1.50 a.m. with about 35 people on board including the nine-week old, Millvina Dean. At the same time, Lightoller supervised the launching of Boat No. 4 with 42 people on board. American millionaire John Jacob Astor was refused a seat on the boat by Lightoller who had allowed his wife on board.

All the wooden lifeboats had been launched and there were only the collapsible Engelhardt lifeboats left. Murdoch and Wilde oversaw the launch of Collapsible C with 44 people on board. A group of stewards and Third Class passengers rushed the boat trying to get on board and so Purser McElroy fired two warning shots in the air whilst Murdoch tried to hold the crowd back.

Ismay helped round up women and children and brought them to the boat. Captain Smith ordered Rowe to take charge of the boat and it was launched at 2.00 a.m. with 43 people on board including Ismay, who jumped in at the last minute as it was being lowered. His cowardice behaviour earned him the nickname Joseph “Brute” Ismay.

“Every man for himself”

Just after 2.00 a.m., Captain Smith went into the Wireless Room and relieved the two wireless operators saying:

“Men, you have done your full duty. You can do no more. Abandon your cabin. Now it’s every man for himself. You look out for yourselves. I release you. That’s the way of it at this kind of a time. Every man for himself.”

With only one boat left, Collapsible D, Lightoller quickly recognised that many passengers were still on board and most were doomed. He and other officers had previously withdrawn firearms from the store and decided to take no chances. They formed a ring fence around the boat and only let legitimate passengers get into the boat. The boat was lowered at 2.05 a.m. with 25 people on board.

By 2.15 a.m., Lightoller and Moody tried to release Collapsible Boats A and B from the roof of the officer’s quarters. They made makeshift ramps from oars and spars and slid the boats onto the Boat Deck. Harold Bride, went to assist with the launch of a collapsible boat.

Unfortunately, the boat broke through the ramp and landed upside-down on the deck but there was no time to right it as the Titanic began her final plunge. Water swept across the Boat Deck and washed Collapsible B overboard. Lightoller took command of the boat. Harold Bride, and Colonel Archibald Gracie were on the boat.

Bride, returned to the Wireless Room to find a stoker trying to steal Phillip’s lifebelt whom he killed. Both men left their post to escape. Bride, survived but Phillips did not. Many writers state that Phillips made it to the overturned Collapsible B and died from exposure as reported by Bride, and Lightoller, who wrote in his autobiography in 1935, “Titanic and Other Ships,” “…I think it must have been the final and terrible anxiety that tipped the beam with Phillips, for he suddenly slipped down, sitting in the water, and though we held his head up, he never recovered. I insisted on taking him into the lifeboat with us, hoping there still might be life, but it was too late.”

Colonel Gracie wrote in his 1913 book, “The Truth about the Titanic,” that Lightoller and Bride’s account at the Inquests were incorrect and that neither of them saw or actually knew that Phillips was on the overturned boat. A crewman’s body was recovered from the boat but he was not named as Phillips. It is probable that Phillips died in the water and did not reach a lifeboat.

Collapsible A was washed overboard as well and was partially submerged and dangerously overloaded. Only 12 or 13 were rescued by Collapsible D, the rest died of exposure.

Most of the remaining passengers were trying to reach the stern, which by now was sharply rising. Chandeliers throughout the Titanic hung at obscure angles. Tables and chairs slid along rooms and the sound of smashing plates from the galleys would be heard.

Thomas Andrews was reported to be last seen in the First Class Smoking Room. Not wearing his lifebelt, he knew the end was near. Outside, the Titanic’s Band still played on. The Bandleader, Wallace Hartley conducted Ragtime whilst the evacuation took place and finished with a rendition of “Autumn” shortly after 2.15 a.m.

At 2.10 a.m., the water had reached the forward end of the Boat Deck where Captain Smith was standing on the bridge. The great glass dome over the Grand Staircase gave way. Seawater poured all the way down to E-Deck. The Titanic lunged forward thus sealing Captain Smith’s fate.

The Titanic's lights went out, then came on again briefly but finally extinguished at 2.20 a.m. The tilt of the stern grew. The forward funnel toppled over with a mighty crash. Passengers still on board clung to objects on the stern for security. For a moment, the Titanic stood perpendicular in the water. Her propellers glistened by the moonlight. She then started to plunge forward. Suddenly she was gone. There was an eerie silence amongst the survivors in the lifeboats. Few could believe that the Titanic had sunk before their very eyes and that it had cost the lives of so many loved ones.

The Californian’s Second Officer, Herbert Stone, could see the ship no more. At 2.20 a.m., he reported the missing ship to his captain and carried on with his watch.

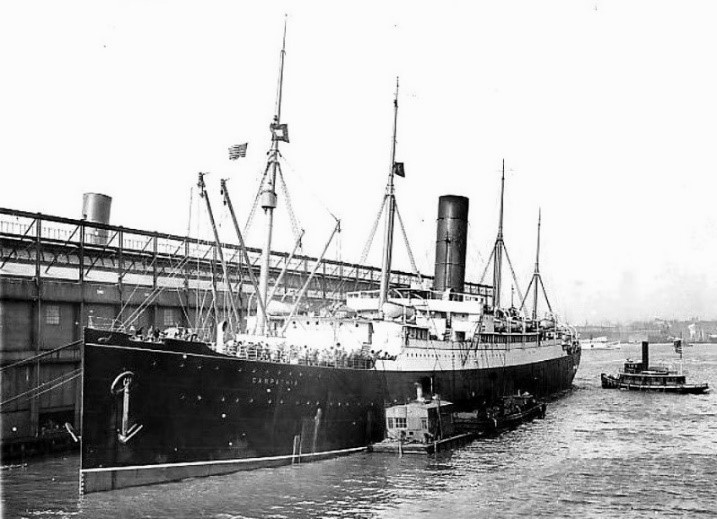

Rescue by the RMS Carpathia

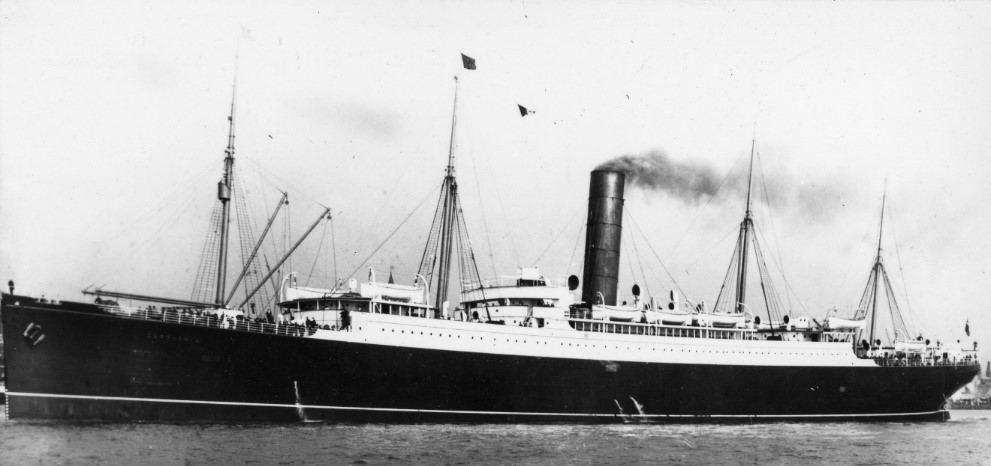

The Carpathia, owned by the Cunard Line, was sailing from New York City to Fiume (now Croatia).

As soon as the Carpathia’s Wireless Operator, Harold Cottam, intercepted the Titanic’s distress messages, he woke the captain to explain the urgency of the matter: he had “received a distress signal from the Titanic requiring immediate assistance.”

As soon as her captain, Arthur Henry Rostron, heard that the Titanic was in distress, he immediately ordered the course of the ship to be changed to intercept the Titanic, although 60 miles from her.

He told the chief engineer “call another watch of stokers and make all possible speed to the Titanic, as she is in trouble.”

At the Inquiry, Rostron testified that the distance to the Titanic was 58 nautical miles or 67 miles and that it took the ship three and a half hours to reach the site. Of course, by the time he reached the coordinates given by the Titanic’s wireless team the ship had already sunk.

She arrived at the scene at 4.30 a.m., over two hours after the Titanic had foundered. Nevertheless, despite the delay and bitter cold she rescued 705 survivors (but one died shortly afterward) from the sea and 14 lifeboats.

Shortly after 5.00 a.m., Captain Lord received a wireless from the Frankfurt that the Titanic had sunk. Upon hearing the news, he joined in the search for bodies and survivors alongside the Carpathia.

The Frankfurt also arrived at the scene at 11.30 a.m. offering help but Captain Rostron explained that there was nothing more anyone can do and the German ship left. The Russian ship Birma was sailing towards the disaster site as the Carpathia passed her on her way back to New York. Signals were exchanged.

Captain Stulpin of the Birma recorded “we met the SS Carpathia going at full speed to the west and exchanged flag signals with her. I asked if everybody was saved and whether we could help in any way. We were told to stand by. I ordered again the enquiry to be made is there any use in our remaining to search further.” He was told nothing more could be done so the ship went on its way.

On 18 April 1912, at 9.25 p.m., the Carpathia arrived at New York. Over 10,000 people were gathered to greet her.

For their rescue work, the crew of Carpathia were awarded medals by the survivors. Crew members were awarded bronze medals, officers were awarded silver, and Captain Rostron was awarded a silver cup and a gold medal (pictured above), presented by Margaret “Molly” Brown.

Captain Rostron was knighted by King George V and was later presented with a Congressional Gold Medal (the highest honour award from the US Congress) after being a guest of President Taft at the White House in 1912.

Replica medal presented to Captain Arthur Henry Rostron

The Cable ship Mackay-Bennett set sail from Halifax, Nova Scotia carrying ice and 100 coffins, 40 embalmers and an Anglican canon to the scene of the disaster. She arrived on site at 8.00 p.m. on 20 April. 51 bodies were found on the first day of the search. Many bodies were in a state of decay after being in the water for five days. The search continued for six weeks and in total 328 bodies were found. 128 were not recognizable – 119 were buried at sea.