RMS Queen Elizabeth (1938)

Launch of RMS Queen Elizabeth

The official contract between Cunard and the government was signed on 6 October 1936. Sir Percy Bates, Cunard’s chairman, told his naval architects that they were to commence designing another ship.

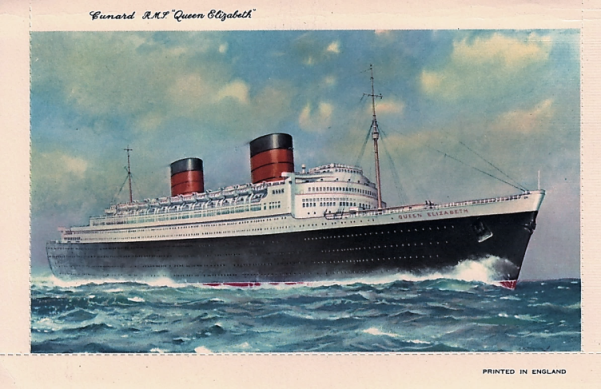

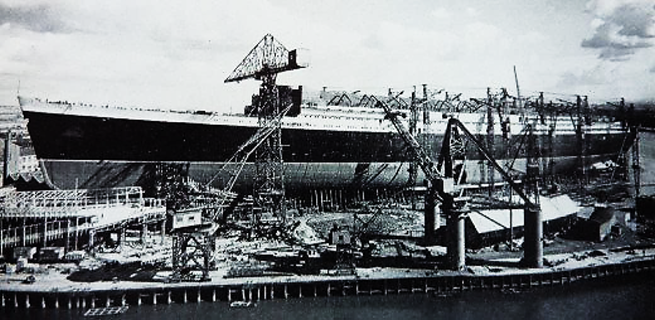

The Queen Elizabeth was built at the John Brown shipyards in the mid-1930s under Hull 552 and was constructed on slip No. 4. She was 1,031 feet long with a beam of 118 feet and had a gross tonnage of 83,673.

Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth, consort to King George VI, accompanied by Princesses Elizabeth and Princess Margaret Rose, attended the launch of the new liner which she named Queen Elizabeth on 27 September 1938. It was exactly four years and a day since the Queen Mary was launched.

Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth gave a speech about peace because war looked imminent.

“I thank you for the kind words of your address,” she said, and continued: “the King has asked me to assure you of the deep regret he feels finding himself compelled, at the last moment, to cancel his journey to Clydebank for the launching of the new liner. This ceremony, to which many thousands of you look forward so eagerly, must now take place under circumstances far different from those for which they had hoped.

I have, however, a message for you from the King. He bids the people of this country to be of good cheer in spite of the dark clouds hanging over them and indeed over the whole world. He knows, too, that they will place entire confidence in their leaders, who, under God’s providence, striving their utmost to find a just and peaceful solution of the grave problems which confront them.

The very sight of this great ship brings hope to us how necessary it is for the welfare of man that the arts of peaceful industry should continue – part in the promotion of which Scotland has long held a leading place. The city of Glasgow has been for Scotland the principal doorway opening upon the world. The narrow waters of the Clyde have been the cradle of a large part of Britain’s mercantile marine, so it is right that from here should go our foremost achievement in that she is a great ship that plies to and fro across the Atlantic, like a shuttle in a mighty loom weaving fabric of friendship and understanding between the people of Britain and the peoples of the United States.

It is fitting that the noblest vessel ever built in Britain, and built with the help of the government and people, should be dedicated to the service. I am happy to think that our two nations are today more closely linked than ever before by common tradition of freedom and a common faith.

While thoughts like these are passing through our minds, we do not forget the men who brought this great ship into being. But then she must ever be a source of pride and, I’m sure, of affection. I congratulate them warmly on the fruits of their labour. The launch of the ship is like the inception of all great human enterprises – an act of faith. We cannot foretell the future, but in prevailing for it we must show our trust in a divine providence and in ourselves.

We proclaim our belief, that by the grace of God, and by Man's patience and good will, order may yet be brought out of confusion, and peace out of turmoil. With that hopeful cry in our heart, we send forth upon her mission this noble ship.”

After the speeches, the Queen was presented with a sixteenth century inlaid casket from Saxony containing a photograph album of pictures taken during the building of the ship. Suddenly there was a huge crashing sound as the hull started to move on its own accord. She had not been christened yet.

The Queen reacted and said “I name this ship Queen Elizabeth and wish success to her and all who sail in her.” The microphone did not work properly and only those close to her could hear her. The Queen cut the red, white and blue ribbon hurtling a bottle of champagne against the bow. It was a close call.

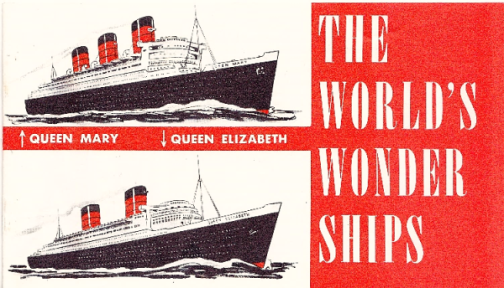

The Queen Elizabeth would be better fitted out than her sister, the Queen Mary. She would be slightly longer by eleven feet and would be 4000 tons heavier. She was the largest ship ever built at that time and would remain so for another 56 years.

Sir Percy Bates gave an address at the ceremony dinner.

“The ship you have just seen launched is no slavish copy of her sister. I described a sister, the Queen Mary, as the smallest and slowest ship that will do the job.” He went on to say, “Naval architecture and Marine engineering have not stood still since we contracted for No. 534 (the shipyard contract number for the Queen Mary) and we tried hard to make use of their progress to get the functional requirements for the sister ship expressed in a smaller hull. We found it impossible. For our schedule we need no more speed than the Queen Mary has got.”

The ship would carry twelve boilers (Queen Mary had 24) and so would only need two self-supporting funnels (instead of 3 carried by the Queen Mary). This would increase deck, cargo and passenger areas. The two funnels were braced internally to give a cleaner looking appearance. The forward well deck was removed.

Following the launch, she was towed to the fitting-out dock at the shipyard in her Cunard colours where she remained until 2 November 1939. Her engines were tested on 29 December 1939. The propellers had been disconnected so that oil and stream operating temperatures and pressures could be measured.

War Career of RMS Queen Elizabeth

Work on the fitting-out was temporarily suspended upon the outbreak of Second World War. She would become a troopship. She was reberthed at the John Brown Shipyard before being moved because the shipyard was the only one of sufficient size to accommodate such ships like the HMS Duke of York, a “King George V” class battlecruisers now in urgent need of repair.

Shortly after noon on Monday 26 February 1940, the Queen Elizabeth moved slowly away from her berth heading downstream. There was an order from the first Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill directing that the vessel should stay away from British waters for “… as long as this order lasts.”

The liner was escorted as far as the Northern Irish coast by aircraft and by four destroyers before she headed into the Atlantic to an unknown destination.

On 3 March 1940, under the command of Captain John Townley, the Queen Elizabeth left the Clyde and headed down the coast to Southampton to be fitted out as a troopship. Several decoys were planted to keep their mission secret.

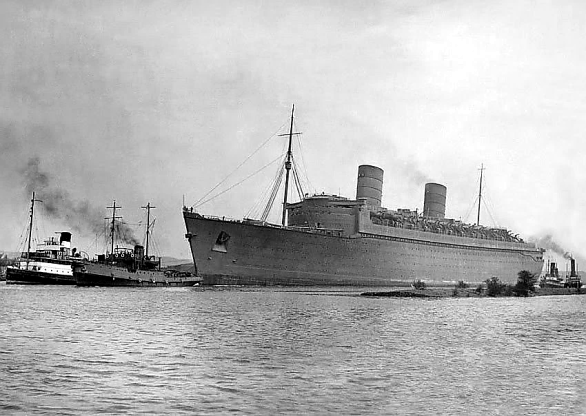

During the short voyage to Southampton, the captain received his orders: sail her directly to New York unfitted-out as a troop ship. She left the Clyde painted in wartime grey (pictured left).

The voyage took six days. The Queen Elizabeth was moored next to the Queen Mary and the SS Normandie. The Queen Elizabeth remained in New York to be fitted with some basic equipment and the launch gear that had still been attached to her hull during the dramatic maiden voyage was removed.

On 21 March 1940, The Queen Mary left New York for Sydney in order to be transformed into a troop ship that could carry 5000 passengers.

On 13 November 1940, the Queen Elizabeth sailed to Singapore to complete her fitting-out as a troop ship. She was completed with anti-aircraft guns and her hull was repainted black although the decks remained in wartime grey.

On 11 February 1941, the Queen Elizabeth set sail to Sydney. She was to join the Queen Mary in transporting troops between Sydney and Suez. During her troopship service, the Queen Elizabeth carried over 750,000 troops, and she also sailed some 500,000 miles (800,000 km).

On 7 December 1941, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. When the United States entered the war, great carrying capacity was needed to transport their forces. The Queen Elizabeth went to Canada for dry-docking and whilst there, the ship’s bottom was cleaned, the interiors fumigated and guns fitted. Once completed, the Queen Elizabeth sailed to San Francisco where she ran briefly aground near the Golden Gate Bridge.

Once her refit was completed, the Queen Elizabeth left for Sydney with 8000 American troops on board.

Each ship usually carried a whole division, with the record set by the Queen Mary on 25 July 1943 with 16,683 troops on board. During these voyages, the ships were carrying lifeboat accommodations for only 8,000 people. This posed a serious risk, but it was one that had to be overlooked.

Adolf Hitler, Chancellor of Germany, offered a reward of $250,000 to any U-boat captain responsible for sinking either of the Queens. In October 1942, Captain Ernst-Ulrich Bruller, the commander of U-407, fired four torpedoes at the Queen Mary, all of which missed.

On 9 November 1942, the Queen Elizabeth was involved in an incident that remains speculative. In the early afternoon, Captain Horst Kessler, commander of the German U-Boat U704, spotted a two funnelled steamer cruising off the west coast of Ireland heading south towards France about six or seven miles away. He identified the ship as being the Queen Elizabeth and fired four Torpedoes. One of them detonated in the water before reaching the ship and was heard by some passengers on board and the other three ran too deep to hit.

The Queen Elizabeth carried on at speed unscathed. Captain Kessler made an incorrect report stating that that the liner had been sunk with all lives lost and Joseph Goebbels, Germany’s Propaganda Chief, broadcasted the news. Following the unsuccessful attacks, the Queens were given the nickname “The Grey Ghosts.”

On 7 August 1945, the Queen Elizabeth left Gourock for Southampton and arrived on the 20 August 1945. Commodore Sir James Gordon Partridge Bisset took over command of the Queen Elizabeth when Captain Fall retired. Thirty four years earlier, Sir James had been the Second Officer on the Carpathia when she raced to rescue the survivors of the Titanic.

On 2 September 1945, the war ended. During it, the Queens had ferried more than two million persons to the war zone. For the next several months, the Queen Elizabeth would transport GI’s and other troops to New York and Canada.

On 6 March 1946, the Ministry of War Transport announced that she would be the first ocean going passenger ship to be released from His Majesty’s Government service. It took 12 weeks on the Clyde at Gourock for her to be refitted out as a passenger liner.

On Friday 8 March 1946 at 8:50 a.m., a fire broke out in the Isolation Hospital on the Promenade Deck. The room was being used as a medical store and contained bottles of methylated spirit and many other inflammable substances. The room did not have any automatic sprinklers. The Southampton Fire Brigade were joined by several other brigades from surrounding towns. It took three hours to extinguish the blaze. The damage was considerable and the repair cost was £1 million (£29.28 million today).

On the 30 March, Cunard’s engineering team began to restore the ships structure. The work took 10 weeks to complete. The cost was borne by the Ministry of War Transport. Cunard paid for any additional work they required. To repair the red paint that had burned away, the hull needed 30 tons of anticorrosion paint to dress her. She was given a white superstructure and orange funnels topped with two thin black bands on the orange of the lower funnel. She was the first British liner to be restored. She was regarded as a “wonder ship.”

Maiden Voyage of RMS Queen Elizabeth

On 7 August 1946, the Queen Elizabeth went into the King George V Graving Dock at Southampton so that her exterior could be inspected: propellers were removed and cleaned, her hull repainted and her anchor and chains repainted.

On 6 October 1946, the Queen Elizabeth left Southampton for the Clyde to begin her speed trials. During the short voyage, Commodore Bisset was satisfied that the ship could comfortably cruise “over 30 knots without straining” and so he was confident that her speed trials arranged for the next day would be a success.

The next day, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth, Princesses Elizabeth, Princess Margaret Rose and a party of distinguished guests went on board whilst the Queen Elizabeth was anchored off Gourock and taken on a tour around the ship.

The Queen enjoyed her time at the wheel and remarked “You know, Commodore, I don’t believe this wheel is really steering the ship at all.” The guests bore witness to the “wonder ship.” They admired her scale and detail of the finish line.

On October 16 1946, the Queen Elizabeth finally set out from Southampton on her maiden voyage as a passenger liner. The crossing was fully booked with 2,228 passengers. In amongst the famous passengers were Russia's foreign ministers, Molotov and Vishinsky, travelling to the first session of the new United Nations.

The crossing took four days, 16 hours and 18 minutes. She averaged 27.99 knots and Commodore Bisset told news reporters that the vessel had “performed beautifully – just like a sewing machine.”

The Queen Elizabeth crossed the Atlantic nine times during the remainder of 1946. Commodore Bisset retired from Cunard in January 1947 and was succeeded by Captain Charles Ford.

On 14 April 1947, the Queen Elizabeth sailed from France to Southampton. There was a thick fog on the English Channel which made visibility difficult. At the Nab, Captain Ford picked up their pilot, Captain Bowyer who was not the usual pilot for these waters. During the manoeuvre, Senior First Officer Geoffrey Marr noticed that the ship was not keeping to the designated channel along the Southampton water.

The captain voiced his concern to the pilot and said that she was turning too slow. The pilot continued to navigate. Within moments, the captain ordered “half astern on the starboard engines!” but it was too late and the ship ran aground. The captain ordered “reverse engines” but it was to no avail.

Fourteen tugs came to the rescue, trying to free her and eventually she slid from her captor. Fortunately, there was very little damage done and Lloyd’s did not have to pay out any money from the £6 million insurance policy. On 31 July 1947, the Queen Mary left Southampton on her first peacetime commercial crossing. The following day, the Queen Elizabeth departed from New York harbour. Cunard's ambition of a two-ship weekly transatlantic express service had become a reality.

It was a golden time for the Cunard Line. Their only rival for a time was the Normandie until she was destroyed by a fire in February 1942. The Queens had Atlantic supremacy.

In 1947, Cunard bought up the remaining White Star Line's (WSL) share in the company and only the RMS Britannic and the MV Georgic remained in the WSL livery.

By 1957 there were just as many passengers being transported by plane than by sea. Cunard did not react to this competition and revenues from the passenger side of the business began to fall rapidly.

Passenger Liners in the 1960s

By 1961, travel patterns had reversed: 750,000 going by ship and 2 million by plane. Cunard’s revenues from passenger carrying continued to fall. In 1962, a £1.9 million loss was reported; £1.6 million in 1964 and £3 million in 1965. The Seamen’s strike of 1966 exacerbated matters.

In order to reduce costs, the Queens’ annual overhaul was postponed until the winter of 1962 when the Queen Elizabeth was taken off the North Atlantic service for one month so that work could be carried out by John Brown & Co costing £450,000. She was given a new cocktail bar to replace the old Cabin Class Lounge. 150 Cabin Class state rooms and cabins were furnished with new colour schemes and the carpets were replaced.

From 1963, she operated more as a cruise liner than a passenger liner. On 21 February 1963, the Queen Elizabeth made her first “cruise” to the Caribbean. If such cruises were successful, the finances of Cunard would improve. Indeed, they were popular, so much so, that further overhauls and improvements were made in 1964 to capitalise on her cruise liner role.

By 1965, pleasure cruising was expanding. Further alterations were planned over a four-month period, including better full air conditioning in both passenger and crew accommodation (essential when travelling around the Mediterranean). Additional private showers and toilets were fitted in 250 Cabin Class and Tourist cabins.

In 1965, the Cunard Line decided to build the QE2 to replace the thirty year-old Queen Mary.

On 16 May 1966, the Queen Elizabeth became one of the first major ships affected by the strike and was laid-up at Southampton for two months: at a cost estimated at over £3.5 million.

On 31 October 1967, the Queen Mary left Southampton on her 516th and “Last Great Cruise.” She was sold to the City of Long Beach, California for £1.5 million where she is still a popular floating hotel today.

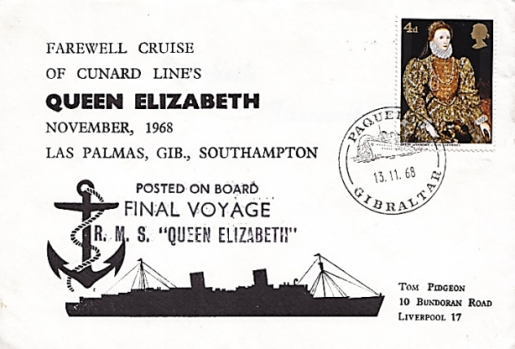

On 5 April 1968, Cunard accepted a bid of £3.23 million for the sale of the Queen Elizabeth from a group of Philadelphian businessmen who planned to moor her off Hogg Island in the Pennsylvania Delaware River. However, as the Delaware River is insufficiently deep, a new site was found for the Queen Elizabeth at Fort Lauderdale in Florida. The Queen Elizabeth’s final round voyage was on 23 October 1968. She sailed from Southampton to New York.

At the same time, Cunard announced that they would inject £500,000 into The Elizabeth (Cunard) Corporation, a new formed company. They hoped this action would enable the Queen Elizabeth to continue to generate meaningful revenues. However, the Philadelphian businessmen were suffering from both financial and organisational problems, so Cunard still owned an 85% share in the ship. The businessman leased the ship from Cunard for approximately £1 million a year.

The Queen Elizabeth arrived back at Southampton on 4 November 1968. It was her all 495th voyage. Her Majesty the Queen wanted to pay tribute to the ship because she had been the “Pride of Britain” for 30 years. On 6 November 1968, Her Majesty was greeted by Commodore Geoffrey Marr and Staff Captain W. J. Law and shown around the ship.

The Queen Elizabeth arrived at Fort Lauderdale on 8 December 1968, to be converted into a floating hotel and visitor centre which opened to the public on 14 February 1969. By a request from Cunard, the “Queen” part of her name was dropped and the ship became known as the “Elizabeth.”

Due to Florida’s climate, the Elizabeth started to show signs of fatigue and her upkeep was proving a huge expense. The owners could not afford the upkeep so she was auctioned off for $8.64 million to Queen Ltd in July 1969.

Unfortunately, a hurricane warning prompted the new owners to partially scuttle the ship to prevent it from being torn from her berth. Queen Ltd became bankrupt and the ship was soon under the hammer once again at auctions held between 9 and 10 September 1970, at the Galt Ocean Mile Hotel, Fort Lauderdale.

Seawise University

A successful bid of £1.33 million (1970 money value) was made by representatives of the Island Navigation Company of Hong Kong owned by the Taiwanese shipping tycoon C. Y. Tung, who wanted to turn her into a floating university that would tour the world. It was an ambitious plan. He would rename the ship the Seawise University.

The Seawise University was neglected for two years and as a result the ship had suffered further severe dilapidation as the Chinese had never encountered a ship as large as the Seawise University. Commodore Marr and chief engineer Ted Philip were asked to come out from retirement to join their old ship in Florida to advise on repairs.

When they arrived in Florida, they were appalled to see the dilapidated state of the “Pride of Britain.”

The Seawise University was ready to sail to Hong Kong in February 1971, but during the voyage there were many problems with her engines. With the help of two tugs she was pulled out to deep water and towed to a safe anchorage. C. Y. Tung visited the ship and ordered that the boilers should be cleaned and restored.

The Seawise University arrived in Hong Kong on 15 July 1971. Once in Hong Kong, work started on turning her into a floating university. Her hull was painted white and the funnels were painted orange. The boilers were reconditioned and restored to their former glory.