Introduction

RMS Olympic (1910) and RMS Titanic (1911) had been built. The HMHS (His Majesty's Hospital Ship) Britannic was the third “wonder ship” to be built. There is some debate whether she was originally planned to be named "Gigantic", but as it can be seen on the name plate on the main picture above it reads "Britannic". It is argued that due to the loss of the Titanic, her owners changed her name to the Britannic. The WSL realised that in order to be the most popular choice for passengers making transatlantic crossings, the new liner would need to be more luxurious than her sisters.

After the sinking of the Titanic, large-scale alterations were made to her design and she would carry enough lifeboats to accommodate every passenger and crew.

Construction

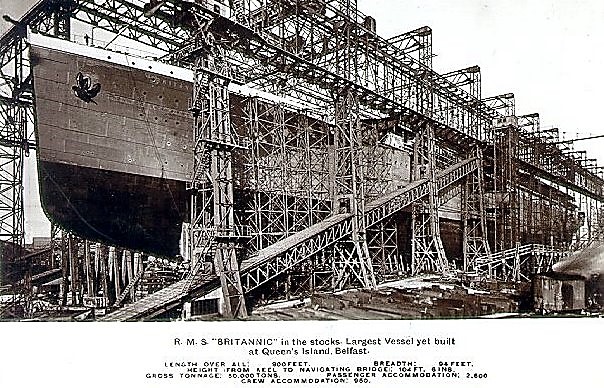

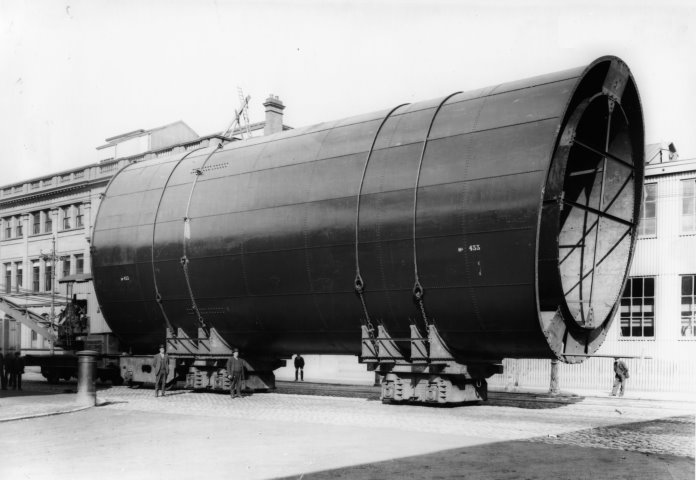

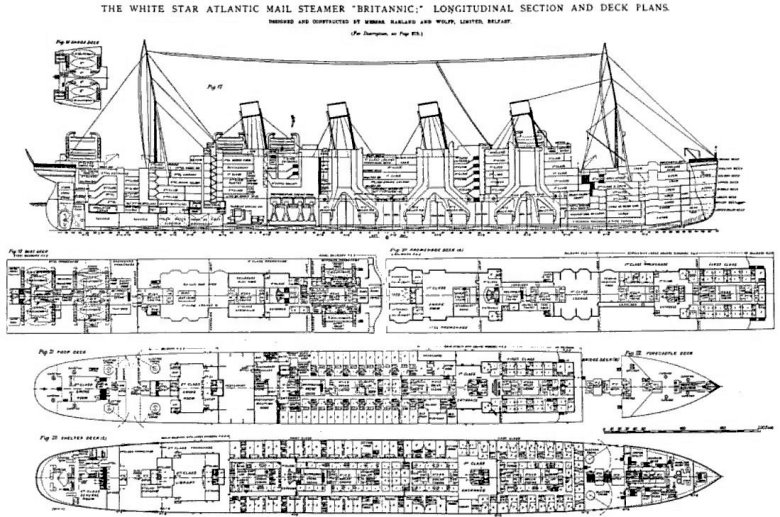

The Britannic was built by Harland and Wolff under keel number 433 which was laid on 30 November 1911. She was 882.9 feet and (a fraction longer than the Olympic) with a beam of 94 feet. Her gross tonnage was 48,158. She had 9 decks. She was fitted with a double skin hull which ran for the full length of the boiler and engine room compartments.

An extra bulkhead was added to make 17 compartments and five of them were extended to the Bridge Deck some 40 feet above the waterline.

These modifications should in theory, prevent her from sinking in under three hours.

The boiler room and engine rooms of the Britannic were almost identical to those of the Olympic. Her turbine engines, built by Harland & Wolff, not by John Brown & Co, could generate 18,000 horse power.

The aft Shelter Deck was enclosed enabling the Third Class passengers to enjoy a covered area of exterior deck which differed from the Olympic’s. The Third Class Smoking Room was placed above the Third Class General Room giving an impression of a bigger stern.

She carried 48 open lifeboats; 46 of them would be 34 feet long (making them the largest lifeboats ever placed on a ship). Two would be motor propelled and carried wireless sets. Two 26 feet cutters were located at both sides of the bridge.

The interior of the ship hardly differed from the Olympic and the Titanic except that the designers added extra delights throughout the ship for every class. The Second Class was given a gymnasium and many of her private rooms were fitted with private bathrooms.

Launch of HMHS Britannic

On the 26 February 1914, the Britannic was launched. At 11.10 a.m., a rocket signalled the commencement of the launch ceremony and workmen removed the blocks which kept the hull from slipping into the water. At 11.15 a.m., with the help of 20 tonnes of tallow, train oil and soft soap, she moved down the slipway. She took 81 seconds to stand afloat.

Following her successful launch, she was towed to the Abercorn Basin, Belfast to start her fitting out, pulled by the tugs Herculaneum, Huskisson, Hornby, Alexandra and the Hercules.

The British press were enthused and described her as “a twentieth century ship in every sense of the word” and “the highest achievement of her day in the practise of ship building and marine engineering.” Hundreds of tradesmen commenced the task of fitting out: electricians, plumbers and carpenters.

To the WSL, progress was slow and poor. On 2 July 1914, they announced that the Britannic would not be ready for her maiden voyage until early spring 1915. Amongst the reasons for delay was finance. Harland and Wolff was owed £585,000 by the IMM.

If this had been paid on time progress on the ship would have been quicker and on schedule. IMM’s finances were significantly acute that for nearly a year the Britannic was left with no work being carried out.

First World War Service

In August 1914, war was declared on Germany and Austria-Hungary by Britain, France and Russia. This would change the nature of the Britannic’s service.

Both the Olympic and the Britannic were placed together in secure holdings at Belfast whilst their owners awaited the ships to be called for government duty. Both ships remained in Belfast for ten months.

The British government requisitioned the Britannic on the 13 November 1915 to be a hospital ship with orders given to transport wounded soldiers back home.

The Britannic’s fixtures and fittings were stored until after the war and instead she was fitted out as a floating hospital. Her First Class dining rooms were converted into operating theatres and main wards. B-Deck housed the medical officers and other staff. The ship was fitted out to carry 3,309 people.

She had stood so long at Belfast that outstanding major works were needed. Her lifeboats installation had not been completed and so six Welin type davits were installed. Each one could load one open and one collapsible lifeboat.

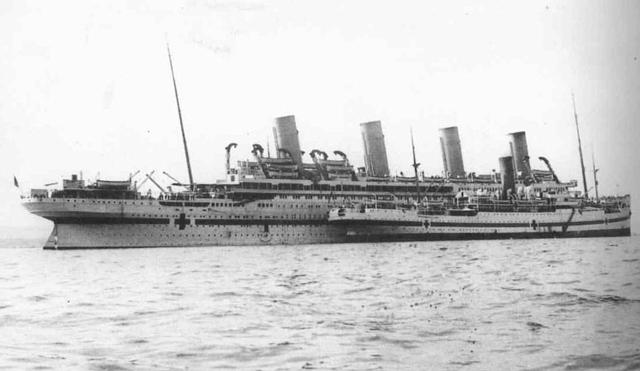

Her hull had to be repainted after standing in water for so long. It was painted in the internationally recognised colours of a hospital ship. A green band was painted on each side of the ship broken by three giant red crosses to identify her as a hospital ship providing her with a safer passage to wherever she was going. She was given ship number 9618.

The Britannic left the Irish Sea on route to Mudros on 23 December 1915. It was her maiden voyage, quite a contrast from the maiden voyages of her sisters. Her voyage was successful and for nearly a year made several more until disaster struck.

The Sinking of HMHS Britannic

On 12 November 1916 at 2.23 p.m., the Britannic left Southampton for her final voyage under the command of Captain Charles Bartlett (also known as the “Iceberg Charlie”) with his assistant Captain Harry William Dyke.

The ship steamed to Naples and arrived on Friday morning (17 November). She took on board more coal and water. Bad weather prevented an early departure. She was secured in Naples for two days until Sunday when Bartlett decided the weather was suitable for departure. On board usual church services were held to pray for the wounded and the end of war.

At 8.00 a.m. on Tuesday 21 November, Bartlett changed course for the Kea Channel with Chief Officer Robert Hume and Fourth Officer Duncan McTavish on the Bridge. All seemed well, but suddenly, at 8.12 a.m. a loud explosion echoed around the ship. Reverend John A. Fleming, the Presbyterian Chaplain, described the blast as “if a score of plate glass windows had been smashed together.”

Captain Bartlett knew he had to act fast after the explosion between cargo holds 2 and 3. He knew that the ship’s watertight skin extended as far as Boiler Room No.6 and that the blast damaged the bulkhead between holds 2 and 3 and bulkhead hold No. 1.

He ordered the watertight doors closed but the doors between Boiler Room 5 and 6 failed to close properly. Water travelled further aft and as a result would prove disastrous. It was customary that during shift changes certain watertight door would remain open enabling the crew to enter and leave the boiler rooms.

Within minutes of the explosion, water was pouring in so fast that the ship developed a serious list to starboard. The situation was becoming more serious by the minute. Within 15 minutes after the explosion, the portholes on E-Deck were under water. Unfortunately, many had been opened by the nurses to let fresh air circulate the wards for the benefit of patients. This added to the emergency. Meanwhile, Captain Bartlett thought he would have enough time to beach the ship on the nearby island off Kea. However, the list to starboard and the weight of the rudder hindered the ship's progress in the water. Once he realised that the ship could not make the coast he ordered the engines stopped and the lifeboats lowered.

A distress signal had already been sent by the Britannic giving their position and the British destroyer Scourge and the French tugs Goliath and Polyphemus all responded and headed to the Britannic. The British auxiliary cruiser Heroic also re-plotted her course to join the rescue.

The lifeboats had begun to be lowered. Captain Dyke arranged the lowering of the boats on the starboard Boat Deck. Fifth Officer Gordon Bell Fielding swung out two boats on the portside but left them both hanging six feet from the water. He realised if he dropped them the ships great propellers would suck the little boats into her wake and kill everybody in them. Two other boats which left without permission were destroyed by the propellers.

Mrs. Violet Jessop, one of the stewardesses on board, told a remarkable story. She had been on board when the Olympic collided with the HMS Hawke, and had also been on board the Titanic. She seemed a very fortunate lady with the same number of lives as a cat! As she had seen the effect of the giant propellers twice before, she jumped from the lifeboat before it was sucked into the propellers. The suction was still too great and she was pulled in but luckily was thrown clear of danger. When she rose to the surface, she hit her head on the lifeboat but was dragged to safety by survivors in another. Captain Bartlett heard of the incident and ordered the propellers to be deactivated, thus preventing more loss.

At 8.35 a.m., Captain Bartlett gave the order to abandon ship. Three more boats were lowered but the starboard side list prevented some others being lowered. Captain Bartlett sounded the ships whistle one last time. As she continued to fill with water, the Bridge soon submerged, from which Captain Bartlett simply walked off the platform into the sea.

As on the Titanic, the engineers remained at their posts until the last minute before escaping through the funnel casing of the fourth stack. The Britannic had not long to live and began to keel over. Survivors in the boats could hear internal explosions.

The Britannic finally rolled over at 9.07 a.m. There were 35 lifeboats and hundreds of people frantically swimming in the water. In 55 minutes, the 48,158 ton ship had sunk.

Captain Bartlett swam to a nearby ship and quickly began co-ordinating a rescue mission to save those in the water.

At 10.00 a.m., the Scourge saw the lifeboats and within 10 minutes started to pick up survivors. The Heroic was also on the scene and doing the same. She picked up 494 survivors. There was a total of 625 crew and 500 medical officers on board at the time of her sinking. A total of 21 crew and 9 Officers and men of the RAMC (Royal Army Medical Corps) were killed in the disaster. A much lower mortality rate ratio than her sister, the Titanic.

What sank HMHS Britannic?

After she sank, several rumours and theories developed to explain how a virtually unsinkable ship could sink in under an hour. Two of the most common are discussed below:

She was hit by a mine

During her penultimate visit to Mudros, the Britannic was observed by the German Submarine U-73 lurking in the deep waters of the Kea Channel on 28 October 1916. U-73 laid mines in the channel. The captain of the German sub decided to plant mines along the Kea side of the channel because he noticed that all vessels preferred that stretch of waters to pass. He laid two mine barriers, each consisting of six mines. The Britannic would cross the mine barriers in future voyages and when doing so would hit one of them.

Sabotage: Enemy spies planted explosives on board Britannic2 which were detonated causing the sinking

There is a conspiracy theory that German spies on board the Britannic planted explosives to detonate during crew shift changes whilst the ship’s watertight doors were open, making her very vulnerable and sinkable. Following her sinking, the British Government made allegations against the German authorities for sinking her unlawfully; she was clearly identifiable as being a hospital ship.

The Geneva Convention prohibited the carriage of weapons on a hospital ship. The German fleet could sink an enemy ship taking weapons to their troops. The German authorities accused the British government of transporting munitions on hospital ships and cited Adalbert Franz Messany’s testimony for confirmation.

Messany, a 24 year old Austrian, was in Egypt when the War broke out and as an enemy to Britain, he was interned. He became ill and was taken to Mudros to be transported on the Britannic. On board, he was able to witness the handling of packages etc. and many other activities. He even spoke to some soldiers about shift changes and heard about the opening and closing of the watertight doors.

Messany spoke to the authorities in Vienna and apparently provided proof that hospital ships were being misused and he listed 22 examples including having seen about 2,500 English soldiers wearing ordinary uniforms who were being transferred on the Britannic to active service elsewhere, who were not sick or wounded. Weight was given to his allegations because he quoted some officers on board (Reg Tapley and Harold Hickman). The crew defended themselves but the damage had already been done.

Following the sinking of the Britannic, the British newspapers accused Germany of every atrocity imaginable. In January 1917, the Germans declared that they would sink any ship they thought to be an enemy. The answers to these two theories could not be properly answered until the wreck was discovered and the cause of the explosion determined. Was she sunk by an internal or external explosion?

Where is the wreck?

The Britannic’s official position was recorded in 1947 as being 2.5 nautical miles west of Angalistros Point on the Island of Makronisos. In 1960, the British Admiralty confirmed the position of wreck 101502722 (her official wreck number) within a fraction of a degree.In 1975, William Tankum of The Titanic Historical Society, asked Jacques Cousteau to dive and explore the wreck. He found the ship on 3 December 1975, nearly 6.75 miles east of the Admiralty position. Her position is 37°42'05''N, 24°17'02''E.

Were the British authorities deliberately withholding the true position of the ship preventing its discovery, thus hiding a secret?

Exploring the wreck

Jacques Cousteau returned to the wreck site in September 1976. She lay 390 feet at the bottom of the Channel. In those days, technology was not as developed as it is today and his dives relied on breathing apparatus not submersibles. Each dive was limited to fifteen minutes followed by a three hour decompression.

Following Cousteau’s discovery of the ship, many questions were asked: was she carrying munitions? Did a torpedo or mine sink her? Was there an internal explosion? Cousteau did not find any evidence to suggest that she was carrying munitions. It is supposed that he meant that he did not find any weapons on the sea bed.

However, with a total dive time of six hours it is hardly surprising. He did however, notice that there a section of hull plating missing. Cousteau could not say whether this had anything to do with an explosion. Technologies available to him at the time could not determine such matters.

Dr. Robert Ballard’s exploration

The wreck lay undisturbed for another 20 years until Dr. Robert Ballard dived to the ship with state-of-the-art equipment of the day. His mission was to pick up where Cousteau left off. The wreck would be photographed and filmed. One of the film crew members on board was Simon Mills who is a long-standing camera technician. He purchased the wreck in August 1996. His objectives are to conduct a full mapping of the wreck and oversee the controlled retrieval of selected artefacts for conservation and public display. His foresees permanent displays in Belfast and Athens of the artefacts and arrange a number of travelling exhibits (like the Titanic ones). For a full article see Q&A with Simon Mills.

Voyager, the remotely operated vehicle (ROV), was connected to a 3-D imaging system to best bring the ship “to life.”

He found that she was actually in good condition and lies on her starboard side at a list of about 85° (except for the bow, which is more upright). There is a tear down the visible port side of the hull.

Dr. Ballard noticed that some of the plating is bent upward, which could explain an internal explosion forcing the plating to explode outward, rather than a mine blasting the plates inward. However, Dr. Ballard is of the opinion that the bending was caused by the impact of the ship hitting the bottom of the sea floor. The rest of the ship was in remarkable condition. There was still glass over the First Class Grand Staircase. Even the propellers were still in place.

However, Dr. Ballard's six day exploration did not shed new light on what sank her. There was no evidence of a mine anchor. He explored a radius of 500 feet from the ship.

Dr. Ballard is convinced that the tear along the hull near the well deck was a result of structural failure not an internal explosion. If so, it is still unclear why the ship took only 55 minutes to sink. He hoped to return to the wreck someday to send a robot vehicle inside the bow section to learn more about what happened.

Since his visit in 1995, the Britannic has been subjected to other expeditions which have stripped her of many artefacts. The desecration will probably continue because the wreck lies in international waters. It has been suggested that she would become an interactive underwater museum fitted with underwater cameras which would broadcast life pictures of the ship to museums all over the world and perhaps the internet. The Greek authorities restrict the number of dives to the wreck but too much irreparable damage may already have been done.

There have been several dives to the wreck since Dr. Ballard’s expedition. In September 2003, Carl Spencer led an expedition and found several watertight doors were open. It was suggested that the mine strike coincided with the change of watches and the door were opened to facilitate crew movement. It was also argued that the explosion could have distorted the doorframes.

Whilst searching the wreck site, Spencer wanted to confirm the German records of U-73 which confirmed that Britannic was sunk by a single mine, and found several mine anchors. He concluded that ship sank quickly because there were open portholes and watertight doors.

He returned to the ship in May 2009 and on 24 May 2009, while filming the bow of the wrecked Britannic, Carl Spencer was killed in an accident. It is believed that he suffered an attack of the bends, which can occur when divers surface too quickly and nitrogen bubbles form in the blood supply.

Other expeditions have been scientific which have examined the colonies of iron-eating bacteria and have tried to calculate the rate of decay of the ship.

Britannic is thought to be in a better state than her sister because the bacteria act as a preservative turning the wreck into a man-made reef.

For pictures of the wreck site please click here: www.wreckdiving.gr