The SS Great Britain (1843)

introduction

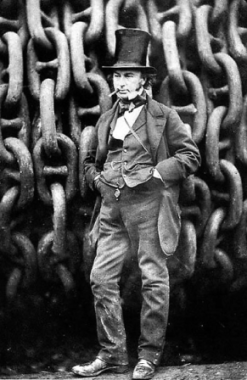

The SS Great Britain was advanced for its time. She was designed by the Victorian Civil Engineer, Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806-1859) pictured here, who already built the highly successful Great Western in 1838, one of the first pioneering examples of steamers with auxiliary sail.

Brunel’s company, The Great Western Steamship Company, wanted to build another ship based on the success of the Great Western. No firm would tender for the building of such uniquely large vessel so the Great Western Steamship Company itself took the job.

A new dry dock was built in Bristol and special construction machinery installed on the quayside. Building facilities at her dock cost £53,081 12s. 9d. and the widening the Bristol locks cost £1,330 4s. 9d.

Brunel teamed up again with Thomas Gruppy, Christopher Claxton and William Patterson although he took the reins and headed the team. Brunel had ambitious plans for the second ship.

Brunel learned from advances in technology and wanted to incorporate them into his designs. His first major change was to give the ship an iron hull rather than a traditional wooden hull. He sent his team to Antwerp on the largest iron-hulled ship, Rainbow (designed by John Laird in 1838), to assess the suitability of the material used.

His colleagues returned convinced that an iron hull was the future. There were several advantages why iron was preferred over wood. Wood was becoming more expensive and actually no longer readily available since the end of the Napoleonic Wars, which had denuded Southern England of her forests and iron was getting cheaper. Iron hulls were not subject to dry rot or woodworm and they did not weigh as much as wood and were far less bulky.

The main advantage of the iron hull was its significantly greater structural strength. Wooden-hulled ships tended to be only about 300 feet because the flexing of the hull as waves pass beneath it (hogging) becomes too great. Iron hulls are far less subject to hogging and so could be built longer. Brunel kept this in mind, and every draft that he did, the ship grew in size. By the fifth draft, it had grown to 3,400 tons, over 1,000 tons larger than any ship then in existence.

When completed, the Great Britain had a gross tonnage of 3443 berthed (1010 net registered). She was 322 feet long with a beam of 51 feet. She could carry 252 passengers with berths (360 could be carried if necessary, but not all with berths); 26 single cabins and 130 Crew. She could carry 1200 tons of coal. Her construction cost was £117,295 6s. 7d.

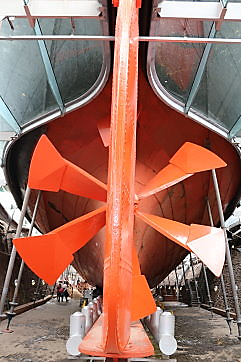

In early 1840, the revolutionary Archimedes was completed and sailed to Bristol. She was designed by Sir Francis Pettit Smith and was the first screw-propelled steamship. Brunel took an immediate interest in the new technology and wanted to improve efficiency with the paddlewheel. Sir Francis Smith agreed to loan the Archimedes to Brunel and together they undertook trials and tests.

Sir Francis Smith suggested a four-bladed propeller to maximise efficiency but Brunel fitted a six-bladed propeller to the Great Britain. The expense of utilising the new technology deferred the launch of the ship by nine months.

The Great Britain was a pioneer ship: she was the first ocean-going screw-propelled ship; the first iron ship to cross any ocean and the first ship fitted with a six-bladed propeller. She was fitted with a semi-balanced rudder, wire rigging, an electric log, a double bottom, transverse water-tight bulkheads, golding masts and a hollow wrought-iron propeller shaft.

Sail would only be used to save coal and when the wind was strong enough.

Launch of SS Great Britain

The Great Britain was launched on 19 July 1843, in the presence of Prince Albert. The date is auspicious as it was the same day on which she returned to Bristol on a floating pontoon in 1970, in the presence of Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, who had played a big part in her return and restoration.

A selection of local dignitaries, including the Marques of Exeter, Lords Wharncliffe, Liverpool, Lincoln and Wellesley, dined on board in the banqueting room and after toasts were made, they attended the naming ceremony. A first attempt to christen the ship failed because the steam packet Avon, had already started to pull the ship and the bottle of champagne missed the bow by some 10 feet and fell to the ground un-smashed.

Prince Albert grabbed another bottle and threw it at the hull. He had to miss the conclusion of the ceremony because there was of another delay after the tow rope snapped.

Frustrations followed due to another unexpected delay. It had been intended that the ship would be towed to the Thames to complete her fitting out. However, it was realised that the harbour authorities had not carried out the modifications needed to accommodate the ship and her propellers were too large for the shallow river. The ship would remain in the harbour for another year until modifications had been made. The delay was costly for the company.

Interior of SS Great Britain

There were three decks; the upper two for passengers and the lower for cargo. The two passenger decks were divided into forward and aft compartments, separated by the engines and boiler amidships.

In the after section of the ship, the upper passenger deck contained the After Saloon or Principal Saloon, 110 feet long by 48 feet wide, which ran from just aft of the engine room to the stern.

On each side of the Saloon corridors led to 22 individual passenger berths, arranged two deep, a total of 44 berths for the saloon as a whole.

The forward part of the Saloon nearest the engine room, contained two 17 feet by 14 feet ladies' boudoirs or private sitting rooms, which could be accessed without entering the Saloon from the 12 nearest passenger berths, reserved for females.

The opposite end of the saloon opened onto the stern windows. Broad iron staircases at both ends of the Saloon ran to the main deck above and the Dining Saloon below. The Saloon was painted in delicate tints, furnished along its length with fixed chairs of oak, and supported by 12 decorated pillars.

Dining Saloon

Beneath the After Saloon was the Dining Saloon. It is 98.6 feet long by 30 feet wide, with dining tables and chairs capable of accommodating up to 360 people at one sitting. On each side of the Saloon, seven corridors opened onto four berths each, for a total number of berths per side of 28, 56 altogether. The forward end of the Saloon was connected to a stewards' galley, while the opposite end contained several tiers of sofas. This Saloon was apparently the ships most impressive of all the passenger spaces.

Columns of white and gold, 24 in number, with “ornamental capitals of great beauty”, were arranged down its length and along the walls, while eight Arabesque pilasters, decorated with “beautifully painted” oriental flowers and birds, enhanced the aesthetic effect. The archways of the doors were “tastefully carved and gilded” and surmounted with medallion heads. Mirrors around the walls added an illusion of spaciousness, and the walls themselves were painted in a “delicate lemon-tinted hue” with highlights of blue and gold.

The two forward saloons were arranged in a similar plan to the aft saloons, with the Upper Promenade Saloon having 36 berths per side and the lower 30, totalling 132. Further forward, separate from the passenger saloons, were the crew quarters. The overall finish of the passenger quarters was unusually restrained for its time, a probable reflection of the proprietors' diminishing capital reserves.

Maiden Voyage and Career of SS Great Britain

On 26 July 1845, the Great Britain sailed from Liverpool to New York on her maiden voyage five years later than planned. The 3,300 miles were covered in 14 days and 21 hours, at an average speed of 9.4 knots – easily breaking the previous speed record for this journey. Fares for a stateroom ranged from 20 to 35 guineas but she carried only 50 passengers on this trip – many people were still a little afraid of her.

On 27 September 1845, she sailed on her next transatlantic crossing to New York and carried 104 passengers. Unfortunately, she ran into heavy weather, and on 2 October 1845, she lost a mast and on 5 October, she damaged her propeller on the Nantucket shoals. She arriving at New York on 15 October, when repairs were carried out in a dry dock. She sailed from New York to Liverpool on 28 October 1845, but during the crossing it was clear that the propeller was still unrepaired and was unserviceable. Her sails were used for the rest of the stormy voyage. The ship rolled heavily causing great discomfort to passengers.

Further funding was given by the shareholders of the company to rectify the issues. The six-bladed propeller was replaced with the original four-bladed one of cast iron design. The third mast was also removed. Complicated rigging was replaced and two 110 feet bilge keels were added. The ship was out of service for the rest of the year whilst the work was done.

Her second year of service saw several completed trips to New York at good speeds but she was laid up for repairs to her chain drums which had shown sign of wear.

Disaster at Dundrum Bay

On her fifth voyage to New York on 22 September 1846, with 180 passengers and a substantial cargo, disaster struck when she ran aground in Dundrum Bay, County Down, Ireland. It was due to “the most egregious blundering” of her captain. The ship was aground for almost a year. Brunel went to inspect the ship and reported that the ship was “almost as sound as the day she was launched, and ten times stronger in character.” He also remarked “…the finest ship in the world… has been left and is lying like a useless saucepan kicking about on the most exposed shore that you can imagine…”

In August 1847, she was floated free at a cost of £34,000 and taken back to Liverpool, but this expense exhausted the company's remaining reserves. After languishing at the North Dock for some time, she was sold to Gibbs, Bright & Co. former agents of the Great Western Steamship Company, for a mere £25,000. Under new ownership, the ship underwent several alterations and a refit.

The keel had been badly damaged by the impact and needed strengthening. The engines were replaced with a pair of modern and smaller oscillating engines built by John Penn & Sons of Greenwich. They were also given more support at the base to reduce engine vibration.

The chain-drive gearing was replaced with the simpler cog-wheel arrangement, although the gearing of the engines to the propeller shaft remained at a ratio of one to three. The three large boilers were replaced with six smaller ones but with twice the pressure of the old ones. A new 300 feet cabin on the main deck was made and the cargo capacity was almost doubled, from 1,200 to 2,200 tons.

The four-bladed propeller was replaced by a smaller three-bladed model. The bilge keels were replaced by a heavy external oak keel for the same purpose. The five-masted schooner sail-plan was replaced by four masts, two of which were square-rigged.

With the refit complete, the Great Britain went back into service on the New York run.

After only one more round trip she was sold to Antony Gibbs & Sons who planned to place her into England-Australia service.

Australian Service of SS Great Britain

The Great Britain’s first voyage to Melbourne began on 21 August 1852, at the start of the Australian gold rush and despite some coaling trouble the voyage was completed in 83 days. She carried 630 emigrants.

Upon returning to Liverpool in April 1853, further modifications were carried out - the two funnels were replaced with a single small one, and the ship was fitted with new three square-rigged masts and a large bowsprit. These masts were all replaced in a refit in 1857. Also, a new stern frame was installed.

Thereafter, the Great Britain settled down to nearly 20 years of steady passages between Liverpool and Melbourne, in a career that made her the most celebrated ship on the Australia run.

In 1861, the Great Britain carried the first England cricket team to contest the Ashes in Australia. During some light-hearted practice in the saloon, the log records that a bat slipped from the hands of the batsman and flew across the deck to strike another passenger in the face creating the need for attention from the ship's doctor.

Mail and Bullion Carrier

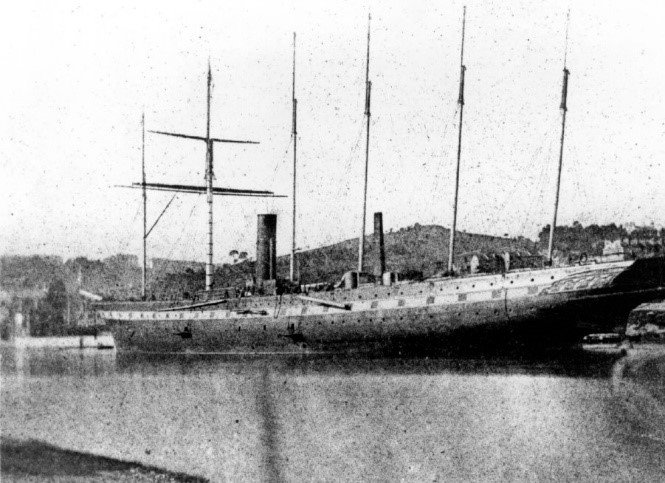

From the start, the Great Britain was destined to be a mail ship and a carrier of bullion which meant that she had to be fast and secure. To deter potential raiders she was painted with false gun ports, as seen in the picture on the next page.

The need to adhere to tight commercial deadlines meant that the outbreak of an epidemic amongst the passengers could be a commercial catastrophe. It appears that the Great Britain was not exempt from episodes of Smallpox, which if declared on arrival at port, would result in the whole ship being quarantined for a period of forty days, thus threatening commercial viability.

On 1 February 1876, the Great Britain was laid up at Liverpool after completing her final Australian voyage and offered for sale in July 1881. Her usefulness as a passenger ship had come to an end.

In late 1882, she was purchased by Antony Gibbs, Sons & Co of Liverpool for use as a cargo ship carrying Welsh coal to San Francisco returning with wheat. The voyages around Cape Horn were long and slow, taking over a year to complete.

The Final Voyage of SS Great Britain

On 6 February 1886, the Great Britain sailed from Cardiff for Panama on “Voyage No. 47.” She left Penarth Dock on 8 February 1886.

On 18 April, as she neared Cape Horn, the ship began to get into serious difficulties in high winds and massive seas. She was taking on serious amounts of water and the hull was under tremendous strain. The crew asked Captain Henry Stap to return to the Falklands but he refused. The cargo shifted and the ship listed to port (which was corrected by shovelling the coal back).

On 10 May, the fore and main topgallant masts were both lost overboard. Three days later, the crew again asked the captain to turn back and this time he agreed. Having battled for three weeks without making any progress, the Great Britain finally turned and ran before the gale, reaching shelter in Port Stanley on 26 May 1886.

It was decided that as her repairs would be too costly and the ship was sold to the Falkland Islands Company (FIC) for use as a storage hulk. The ship floated in Stanley harbour for some 50 years, holding coal and wool for the FIC. By 1937, it was no longer economical to use her as a hulk and she was replaced with another condemned sailing ship, the Fennia.

On 12 April, the hulk was towed to Sparrow Cove where holes were drilled in her sides to ensure that she would never float again.

Salvage and Restoration

In the 1950s, the Director of the San Francisco Maritime Museum, Karl Kortum and a renowned naval architect, Ewan Corlett, became interested in the ship and began researching her history. They were working independently of each other. In 1968 meetings were held in the UK to decide if a British salvage attempt was practicable.

The SS Great Britain Project was formed and Corlett visited the Falklands to survey the hulk with help from the crew of the British ice patrol ship, HMS Endurance. He concluded that she could be refloated. Fund raising began following encouragement from Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh. Jack Hayward, a British philanthropist, pledged £150,000.

The submersible pontoon, Mulus III was chartered in February 1970. A German tug was chartered reaching Port Stanley on 25 March 1970. Mulus III was lashed end on to the port side of the Great Britain and sheerlegs erected on the pontoon deck. Work began on the removal of her masts and the patching of the holes below the waterline.

A large crack had opened up below the forward entry hatch on the starboard side which was dealt with by bolting steel strip plates across it and stuffing the crack with old mattresses gathered from Stanley.

The hulk was pumped out and, once afloat, was towed and pushed onto the submerged pontoon where it was secured to steel dolphins. On the following day, the pontoon was towed into Stanley harbour.

It took 10 days to position the ship onto the pontoon alongside the jetty. On Friday 24 April, at 9.15 a.m., Brunel’s great ship left Stanley on her final voyage home to Bristol. 47 days later the Varius II handed over to Bristol tugs and on 23 June, Brunel’s ship was towed into Avonmouth Docks.

On 5 July, an estimated crowd of 100,000, watched the Great Britain being towed up the River Avon to Bristol. There was a slight wait for a high enough tide to enable her to get through the shallow but on 19 July, she returned to the Great Western Drydock exactly 131 years to the day her first plates were laid there and 127 years since her launch.

SS Great Britain in Bristol Today

Brunel's SS Great Britain is now Bristol's number one visitor attraction, with two museums and the lovingly restored Victorian ship, a leading research centre, a wedding venue and a purpose built conference facility. For more information about the museum click here.