The Maiden Voyage of RMS Olympic

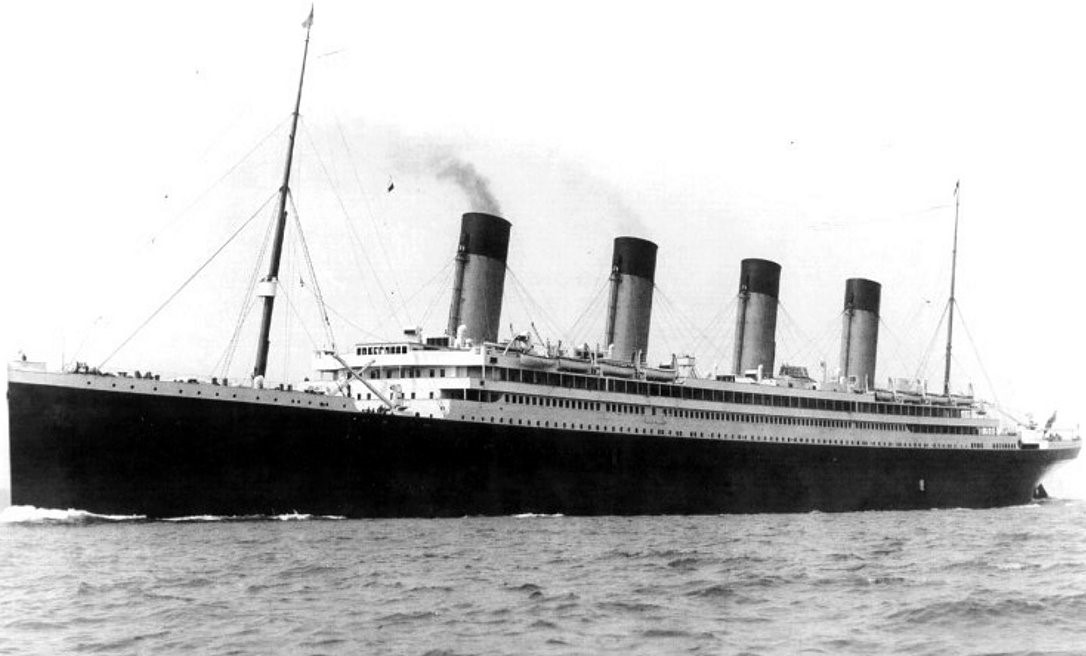

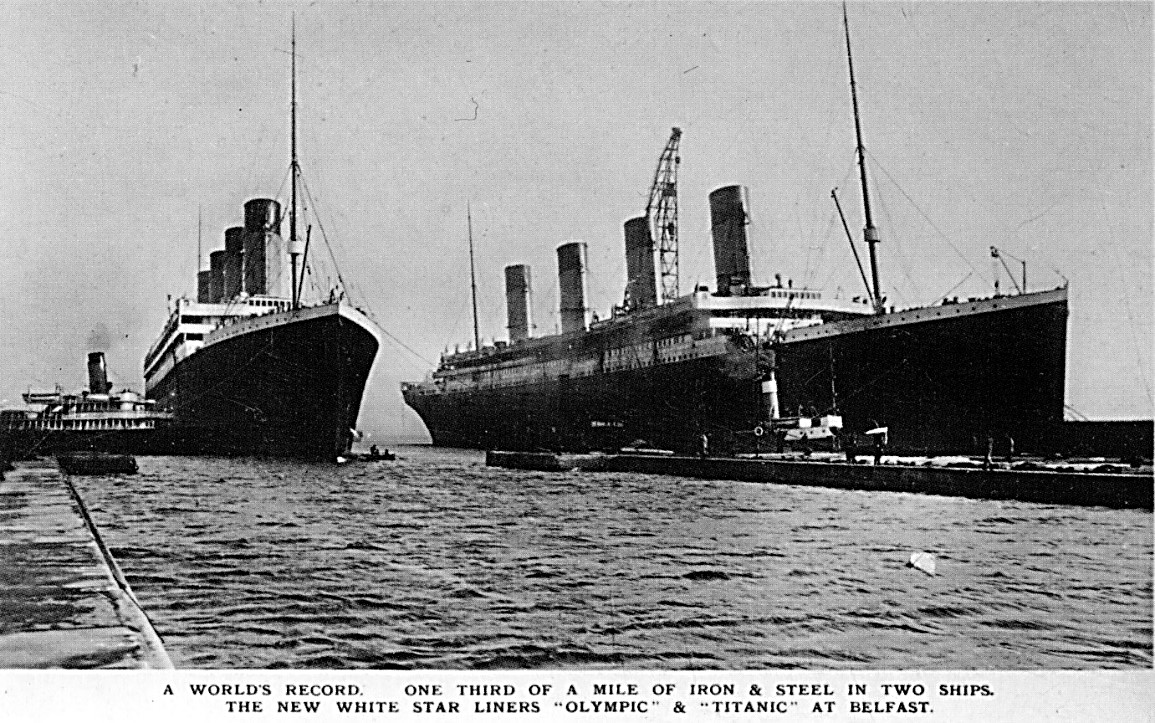

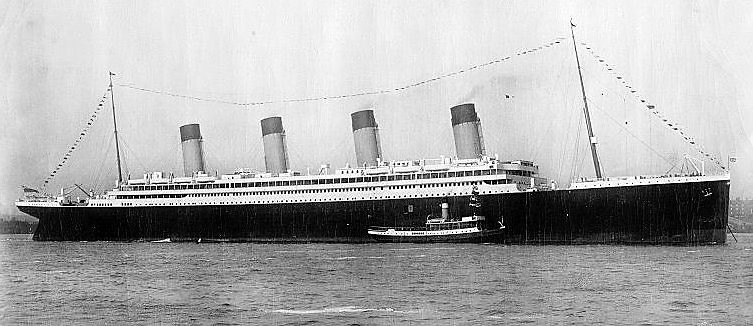

On 2 June, the Olympic sailed to Southampton under the command of Captain Smith and arrived the next day at the White Star Line Dock. The dock opened in 1911 after being specially constructed to accommodate the new “Olympic class” liners. Upon arrival, work began to prepare her for her maiden voyage with vast quantities of food, linen, coal and china etc. loaded on board.

On Wednesday 14 June, she embarked on her journey to New York. The Olympic had beaten the coal strike, which had threatened her voyage. The Olympic handled superbly. Ismay was on board to make any recommendations for change and a journalist from the Times newspaper accompanied the crew on her maiden voyage to record the occasion.

The crossing took 5 days 16 hours and 42 minutes. On some days, she would travel over 540 miles whilst on others she would cover only 430. Her average speed was 21.7 knots. Passengers had travelled in style. Ismay was delighted and could not wait to inform his associate, Lord Pirrie, that the Olympic was “a marvel.”

When she arrived in New York, the waiting crowd were amazed as they had never seen a ship of that size before. Neither had the other ships in New York harbour which found it difficult to keep control in their berths as the Olympic passed due to the wake and suction from the propellers. The tug boat, O.L. Hallenbach, suffered serious damage to her rudder and stern frame when the Olympic's propeller pulled her in. The Olympic was not damaged (except for a few markings to her paintwork). She docked at pier 59.

She left America at 12 p.m. on 28 June 1911 and arrived at Southampton on 5 July. She had completed her journey in a quicker time and averaged 22.5 knots.

By mid-September, Olympic had completed four return visits to New York.

Collision with the HMS Hawke

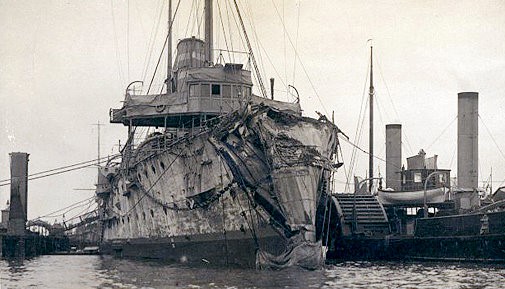

On 20 September 1911, during her fifth transatlantic crossing, the Olympic collided with the Cruiser, HMS Hawke causing considerable damage to both ships.

At 11.25 a.m., the Olympic started her fifth voyage to New York under the command of Captain Smith with 1,313 passengers. By 12.34 p.m., she had reached the Calshot Spit buoy and started manoeuvres to exit the Thorn Canal and into the Solent. She reached the West Bramble buoy at 12.43 p.m. and turned to make a port turn blasting her ships whistle twice. The captain ordered her speed to increase from 11 to 16 knots.

Before the Olympic had finished signalling, the Hawke was off Egypt Point. It was obvious that both vessels were trying to go down the same stretch of water and there was not enough room.

Commander William Frederick Blunt (Royal Navy) altered the Hawke’s position by five degrees to give the Olympic more room. The two ships travelled at about 16 knots and collided with each other. Smith stated that the Hawke's bow reached as far forward as between the second and third funnel.

Navigation Officer Captain George Bowyer stated that the Hawke ran up to the Olympic’s Bridge. The Hawke dropped back but was pulled to Port towards the Olympic’s stern. Blunt ordered the port engine stopped and full astern on the starboard side.

The Hawke crashed into the Olympic's side. The Hawke managed to stay upright but was very close to overturning. Both captains ordered the watertight doors to be closed. Both ships were stopped so that damage could be assessed.

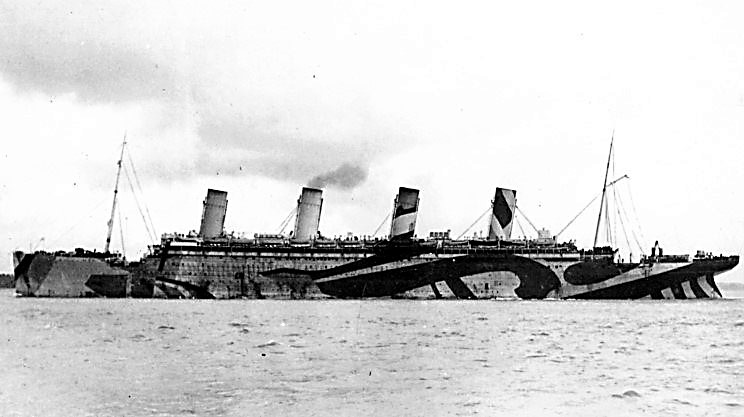

There was a considerable amount of damage to both ships. Above the water-line, the Olympic (pictured below) suffered a twelve feet triangular gash running eight feet deep, fourteen feet above the water line up to D-Deck.

The collision also caused considerable damage to the starboard propeller shaft and chipped the starboard propeller. Under the water-line there was a 7 feet wide pear shape hole punched out of the Olympic which caused two of her watertight compartments to flood.

Her cargo was put ashore and passengers had to disembark at Osborne Bay to find alternative transport (like the Adriatic). The Hawke returned to Southampton for repairs. No one was seriously injured in the collision even though the area of impact affected the Second Class quarters.

It took two weeks to sufficiently patch up the Olympic to enable her to proceed under her own steam to the great dry-dock at Belfast which was the only one in the world large enough to accommodate her. The repairs at Belfast took another six weeks to complete.

The WSL wanted her to be back in service as soon as possible because she was the pride of the company. To ensure this, the Titanic's propeller shaft was used to repair parts of the Olympic, as a consequence of which the Titanic's maiden voyage was delayed.

By 29 November, the Olympic was back in service. Unfortunately, on 24 February 1912 at 4.26 p.m., she lost a propeller blade on an eastbound voyage from New York and had to return to Belfast for repairs. Valuable time was lost during these repairs and the maiden voyage of the Titanic was again postponed from 20 March 1912 to 10 April 1912.

RMS Olympic’s involvement in the RMS Titanic disaster

The Titanic left Southampton, on April 10 1912, on her maiden voyage. The Olympic left New York at 3 p.m. on 13 April. It was expected that the two ships would pass insight of each other.

On the 14 April 1912, the Titanic struck the iceberg and began to sink. Forty minutes after the collision, Captain Smith ordered distress signals to be sent to other ships in the area. Captain Haddock heard all the distress calls but did not realise the extent of the problem until about 1.00 a.m. on 15 April when over 500 miles away from the Titanic. Captain Haddock replied to the Titanic that he was “lighting up all possible boilers.” However, the Titanic was too far away.

The Olympic had no choice but to return to Southampton on Sunday 21 April. After hearing the news about the loss of the Titanic her passengers were in a melancholic mood. Some of whom may have had friends or relatives on board the Titanic. They would want to return home to check the passenger lists posted by the WSL.

Within a few days of return to Southampton, the Olympic had to undergo serious changes. The lifeboat capacity was examined with scrutiny. She was fitted with an extra 24 boats and more crew to man the boats.

The British Board of Trade inspected these changes prior to her next voyage. Her captain, Maurice Clarke, gave her a vigorous inspection and ran mock lifeboat drills to try out the new davits. It took an average of 12.5 minutes to lower each boat. He was impressed with the improvement.

The Olympic should have sailed on 24 April 1912, but the voyage was postponed because the crew refused to sail on a ship with collapsible lifeboats. They insisted on using the conventional open type wooden boats. They were unimpressed that Captain Clarke was satisfied that the Olympic was safe.

However, the WSL did not listen to the crew and even considered replacing them. The Olympic was taken to a secure dock off Spithead to find another crew. It was proved a demanding task (probably because crew hands had heard speculations about the conditions surrounding the sinking of the Titanic). Instead a trade union delegation offered a compromise as it appeared that the debate turned on how safe collapsible boats were after floating in water for some considerable time.

In a trial, six collapsible boats were lowered for two hours and then examined to see how much water they contained. Five out of the six were dry but one had a small leak, although it had taken two hours for water to appear. It would easily have been bailed out during use and it was agreed that the boats were safe. The sixth boat was duly replaced and 168 new crew members joined the ship.

Unfortunately, the original crew were not only dissatisfied with the lifeboats but also with the new crew members. They were seen to be inexperienced and undesirable to be working alongside. They felt so strongly about their position, that over 60 crew members deserted their posts.

On 26 April at 3 p.m., being two days behind schedule, the WSL cancelled the voyage. The Olympic returned to Southampton so that the passengers could disembarked. The next scheduled trip was set for 15 May, giving the WSL enough time to find union approved crew and boats.

On 22 May 1912, the Olympic arrived in New York for the first time since the sinking of the Titanic. As soon as she docked, Senator William Alden Smith, Chairman of the American Congressional Committee, boarded the Olympic to make an inspection. It will be recalled that he was in charge of the American Inquiry into the loss of the Titanic. He wanted to check the capacity of the ship and how her safety features compared with the Titanic’s. He was shown how the lifeboats worked and how they were released.

The watertight doors were also inspected. Senator Smith seemed satisfied. It must have been strange situation for Captain Haddock: his ship was under scrutiny from both his own crew and the American authorities. The whole world appeared to be watching him.

For the next several months, the Olympic made several round voyages from Southampton to New York. On 9 October 1912, she was withdrawn from service pending a refit at Harland and Wolff when modifications were made to incorporate the lessons drawn from the sinking of the Titanic.

Extra davits were installed to accommodate more boats. The lifeboat capacity increased from 20 boats to 64. A major flaw, evident with the Titanic, was that the watertight bulkheads did not run the entire height of the ship. This was corrected and five watertight bulkheads were extended up to B Deck. An extra bulkhead was added making 17 in total.

The Olympic's B Deck underwent a refit as well. Extra cabins were added, including the Parlour Suites. Cabins were fitted with private bathing facilities. The Cafe Parisian was added.

Such modifications meant that the Olympic weighed more than the Titanic with a gross tonnage of 46,359.

By the 22 March 1913, the completely refitted Olympic departed from Belfast and returned to Southampton. She made her first crossing on the 2 April: she was just over one year old.

1913 was a better year for the WSL. Twelve months had passed since the tragedy of the Titanic. The Olympic would not suffer from the design errors of the Titanic and as a result was fitted with better safety measures and gained more popularity.

Captain Smith made nine round trips to New York. He was ordered to give up his position to Captain Herbert James Haddock, because he was going to be the captain of the Titanic. He was one trip off retirement. Captain Smith was at the pinnacle of his career.

The Olympic returned to service in March 1913. She began her fifth voyage (technically her sixth). For the next few months it was plain sailing. Several more trips were made successfully.

RMS Olympic war career 1914-1918

Britain and France declared war on Germany on the 4 August 1914. The war would last for four years. As can be appreciated, there would be many Americans and Canadians and other nationals that did not want to be in a country during war times. Passages were filled; demand exceeded supply.

As a precaution, the Olympic was painted in battleship grey. Her portholes were blocked and the lights on deck were turned off to make the ship less visible. The Olympic’s first war times experience came on 27 October 1914 when she was ordered by the HMS Liverpool to evacuate the crew off the British battleship Audacious, who had struck a mine off Toy Island. In appreciation for his rescue, Captain Haddock was made a Commander.

On 1 September 1915, the Olympic received a telegram requiring her for urgent Government service, and to prepare her for war she returned to Harland and Wolff for further alterations.

To fit a ship out for war is the worst situation for a shipping company. Firstly, governments only paid flat rates for the loan of vessels, like the Olympic (£23,000 per month), and from which, the shipping company had to pay their staff and crew etc. and often ran at a loss as the WSL would find out. Secondly, market values of ships were never agreed between the companies and the Admiralty.

Important questions left unanswered. Who would pay for the ship if sunk? Did they need insurance? The WSL decided to insure the excess amount themselves at their own expense.

The Olympic was ready for service on 24 September 1915 and was given the transport name T2810. Her role was to transport troops to different countries. Her first mission was to Mudros to drop off 6,000 troops. On the way she picked up marooned French sailors from the French steamer Provincia and dropped them with the Aragon.

Her second mission was to Spezia and then back home for 21 December for a well-deserved break. The next trip would not take place until 4 January 1916.

The only other point of interest during her war years occurred on 24 April 1918. The Olympic was sailing the English Channel when, after careful planning by Captain Bertram Fox Hayes (who replaced Captain Haddock), the German U-boat U-103 was struck full on by the Olympic and sank. Captain Hayes was awarded the Distinguished Service Order (DSC).

In November 1918, the German government surrendered. The war may have been over but British troops were still posted all over the world. The Olympic was engaged to bring many troops home.

RMS Olympic Post War Career

By August 1919, the Olympic was ready to be refitted as a transatlantic liner. Work continued until well into 1920. On 17 June, the Olympic was finally ready. A celebration party was held on board on to celebrate the return of the “Old Reliable.” She sailed to New York on 26 June 1920.

The Olympic proved to be more popular than ever. Reports were given on how much passengers used the swimming baths and Turkish baths. Charlie Chaplin sailed on her enjoying the card games in the Smoking Room.

Captain Hayes enjoyed his last voyage on 21 December 1921. He was given the command of the Adriatic. He was at his pinnacle of his career, just like Captain Smith before the loss of the Titanic. Captain Alec Hambleton from the Adriatic would replace Captain Hayes.

In 1927, work had been carried out to the Olympic’s Bridge. Repairs were estimated at £100,000. The WSL did not want to spend so much on her but extensive welding repairs were undertaken. It was clear that the old ship was ageing.

By 1931, once stress cracks appeared near the funnels, the Board of Trade would only certify the ship as safe for a period of six months, presumably to review the situation six months later. However, in March 1933, the Board of Trade gave clearance.

Ticket sales were in decline during the Great Depression. Towards the end of 1932, the Olympic went for an overhaul and refit that took four months to complete and returned to service in March 1933.

Disaster struck for the Olympic on 15 May 1933. Under the command of Captain John Binks, the Olympic smashed into the Nantucket Light Vessel 117 totally destroying it. The height of the Olympic and her speed made it impossible for her not to cause damage to smaller ships. Memories of the Titanic were recalled. Following the Lightship incident, law suit fees generated a staggering $500,000.

In the autumn of 1934, the WSL and the Cunard Line merged. The WSL's contribution to the merger were the giving of 10 ships, one of which was the Olympic. It was suspected though, that the Olympic would not last much longer.

In January 1935, it was announced that Olympic must be retired and withdrawn from service. She stood abandoned for a little over six months.

In September that year, she was sold for £100,000 to Sir John Jarvis, who then sold her to the Jarrow ship breakers Thos W Ward. The Olympic had been in service for 24 years. Her interiors were stripped and sold off London Auctioneers of Knight, Frank & Rutley (Auctioneers). There were 4,456 lots.